When he heard this past weekend that Falcons Ring of Honor defensive end Claude Humphrey had died, George Kunz naturally began sorting through all the mental snapshots he possessed of his old friend and former teammate. One vision dominated.

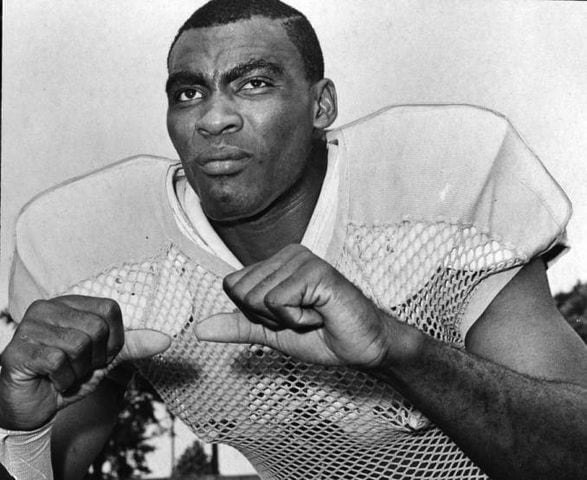

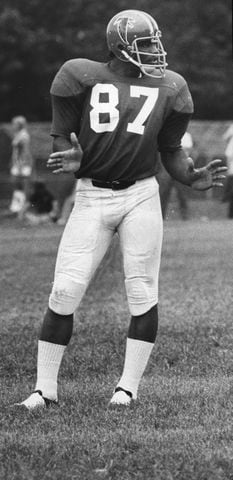

It wasn’t of Humphrey on one of his fierce, up-field assaults, set on rattling some quarterback’s cage. Nor any of the countless practice field scrums that Kunz, the Falcons’ 1969 first-round draft pick at offensive tackle, had with Humphrey, the team’s top pick the year before.

Oddly enough, the memory that stood out the most involved the defense at rest. Of when, during long-ago practice breaks, players would drop to one knee to gather themselves before the sweating resumed. Not all of them, though.

“Claude would always stand up,” Kunz said from his home in Las Vegas. “To me, that was just a reminder to me that Claude was head and shoulders above a lot of other people. He would always stand there while other guys would take a knee. That just wasn’t his style. He was head and shoulders above.”

What better tribute to pay a man, covering the literal and the symbolic?

“A very proud man,” Kunz said. “He took a lot of pride in what he did and in doing it right.”

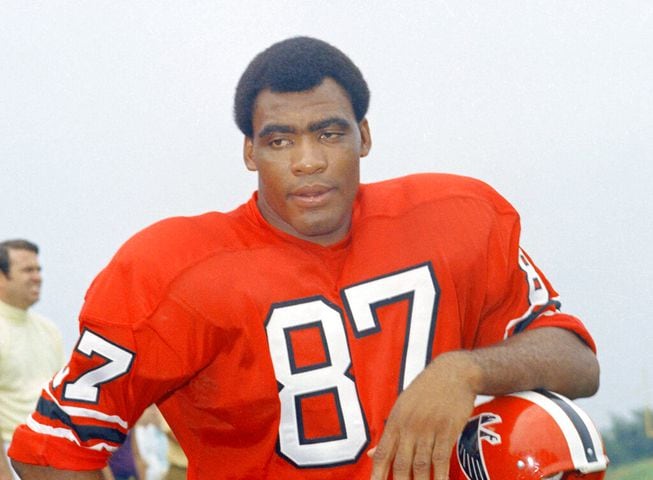

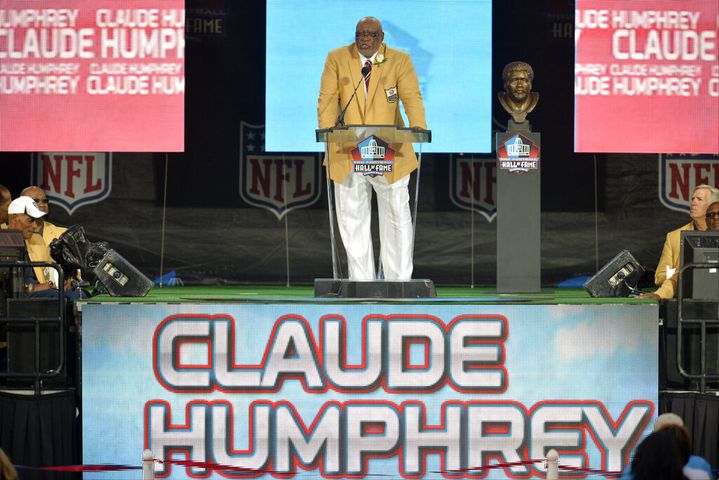

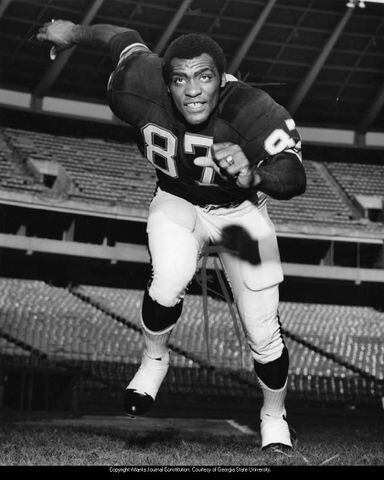

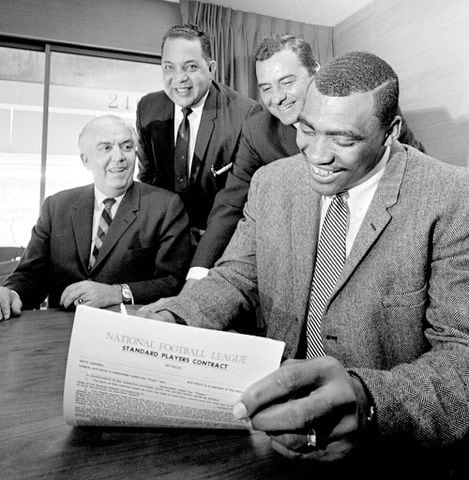

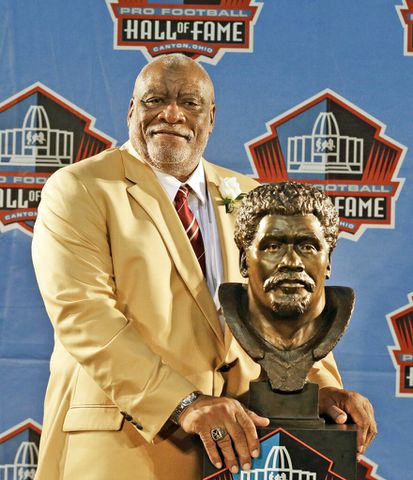

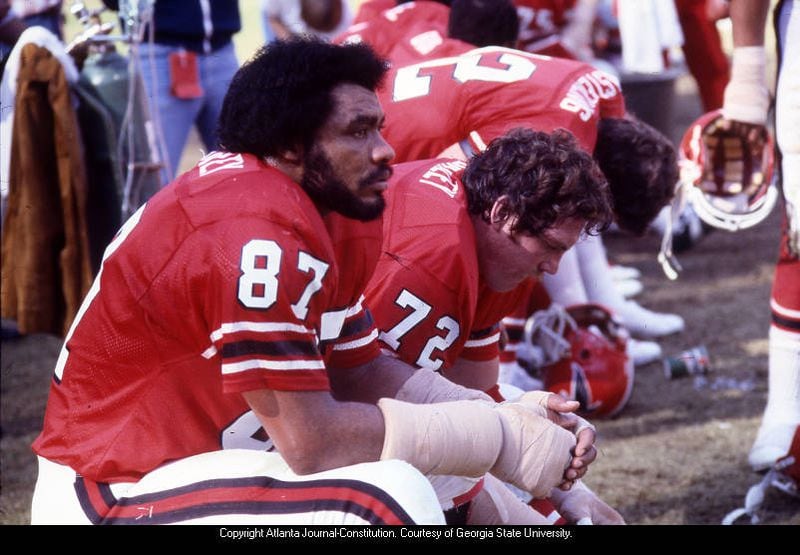

The circle of great, foundational Falcons players is ever shrinking. On Friday, it lost only the second player drafted by the team, along with Deion Sanders, to make the Pro Football Hall of Fame. It took Humphrey – 77 at the time of his death, 70 when he was inducted – multiple decades and multiple ballots before he got to Canton in 2014. That was the price of so much losing with those early Falcons and his ultimate rejection of it.

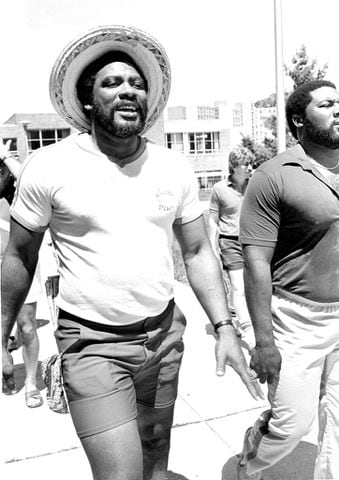

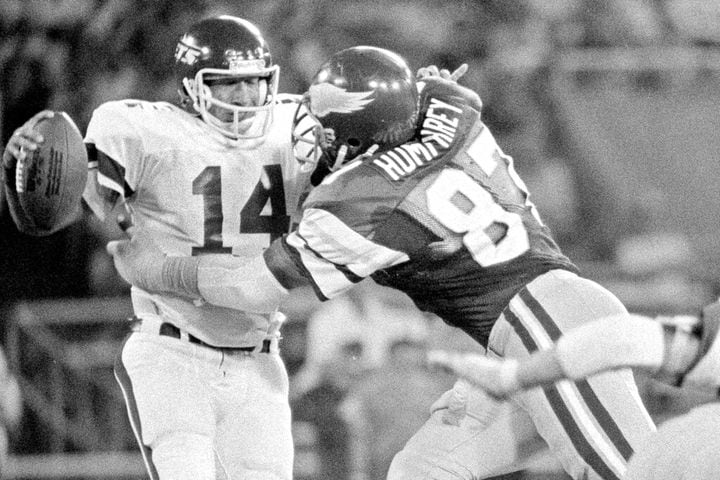

The Humphrey I met at his home in Memphis that Hall of Fame year was someone quick to smile and slow to boast. An outsized man who filled a room with ambient pleasure. The exact same person as described by those who knew him during his playing time with the Falcons (1968-some of ‘78) and Philadelphia Eagles (1979-81).

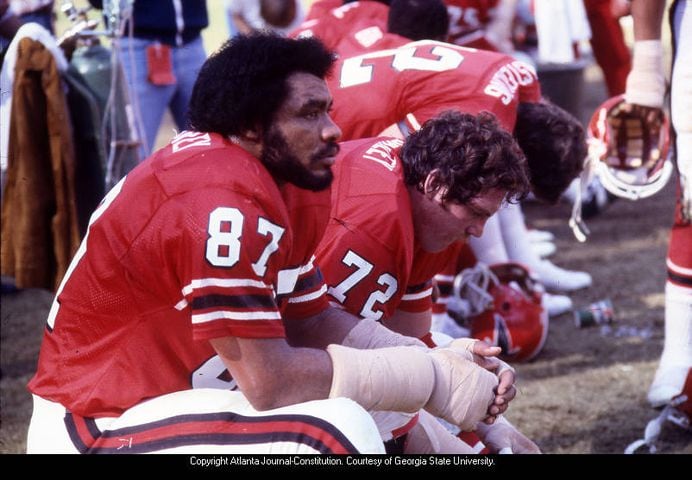

To former, long-time Falcons athletic trainer Jerry Rhea, Humphrey and his close friend tight end Jim Mitchell – who died in 2007 – “were happy, happy people who were the hearts of the clubhouse.”

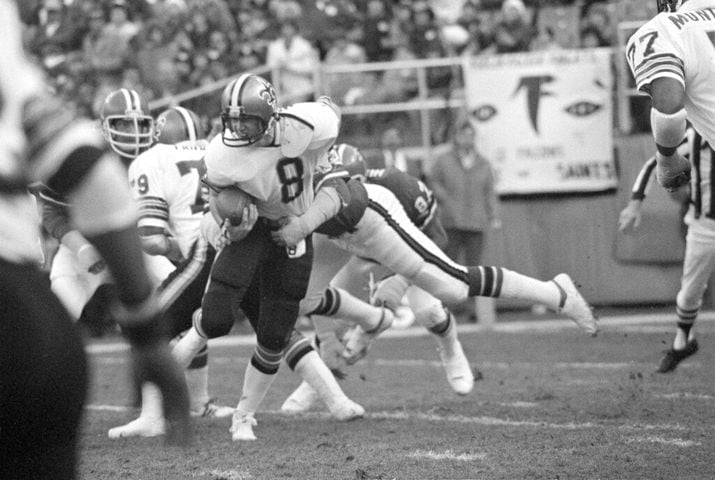

“Then they’d go to work on Sunday and knock your ass off,” Rhea said with a chuckle.

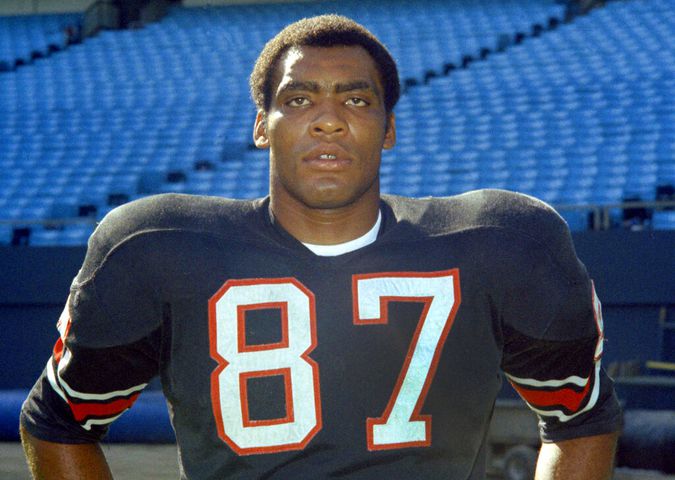

Humphrey’s relationship with Kunz was one of mutual respect and benefit. On one side, Humphrey was a six-time Pro Bowl player who anchored the 1977 “Grits Blitz” defense that allowed just nine points per game. On the other, Kunz was a four-time Pro Bowler while with the Falcons.

“Those two guys would go at it hard in practice. (Coach Norm) Van Brocklin would love it. And they both made All Pro because they made each other better,” former Falcons running back Harmon Wages recalled.

“Claude was extremely bowlegged – not many remember that – but he had a great ability to come up-field and push off with the outside leg and come back inside quickly. If you were setting up to take him outside, you’d be off balance,” Kunz said, beginning to number Humphrey’s physical skills. “Obviously, he was very, very strong. He had long arms, which helps a defensive lineman in terms of keeping an offensive tackle off him. He put it all to good use.”

Humphrey also was good at lightening the load of so much institutional losing – the Falcons never made the postseason during Humphrey’s term with them, going 49-74-3 (not counting the ‘75 season he missed with a knee injury). Kunz recalls getting ready to play one team during the Falcons 3-11 season of 1974 – he can’t remember which, only that it seemed beatable at the time – and telling Humphrey, “If we lose to these guys, we’re really bad.”

Naturally, the Falcons lost. “Coming up the tunnel at Fulton County Stadium,” Kunz said, “I could feel an arm go around me. It was Claude. And he said, ‘George, we’re really bad.’”

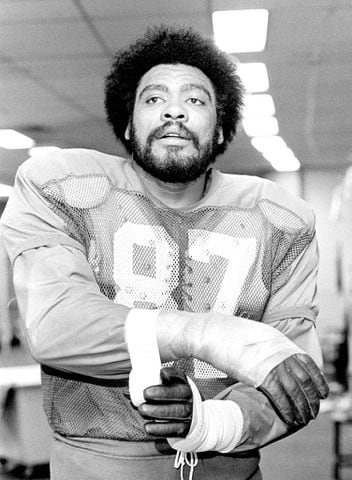

Inside, however, the losing slowly corroded Humphrey’s spirit, until it ate all the way through four games into the 1978 season. He up and left the team and stayed away until he leveraged a trade to Philadelphia the next year. The episode may also have contributed to his long wait before getting the Hall of Fame call.

As he said back in 2014, “One day I was sitting in the locker room and said, you know, this thing isn’t getting any better. I put my stuff in the locker and left, it was just that simple. I wasn’t mad at anybody because there was nothing I could do as a player but do what I did. They said they weren’t going to trade me (then). That was obvious.”

Humphrey came from a time before they tallied quarterback sacks. NFL chroniclers reviewed old game film and deemed Humphrey’s total to be 130, although he always suspected more. But they surely kept a record of wins and losses, and those numbers never favored him with the Falcons. He did, though, make it to one Super Bowl with the Eagles.

More important, Humphrey left behind those who were the better for having known him. Kunz’s life has been full and challenging – post-football he was a fast-food franchisee in Arizona and Nevada, who went back to school and became a lawyer at the age of 63. And that life was improved all the more by its time shared with Humphrey.

Eulogies will flow for Humphrey during funeral services Saturday in Memphis. Let Kunz’s simple and fond remembrance of a lost teammate provide a base:

“He was a great athlete. I knew when I practiced against Claude, I didn’t have to worry about anybody else.

“When I was traded to the Colts (1975), Claude was one of two people (the other being late defensive end John Zook) to call me up and tell me he was going to miss me, that I was a friend.

“He was a good man. I’m proud to call him a friend.”