There’s big business in the new normal of school safety.

The state is giving local school districts more than $450 million in grants to pay for security upgrades, a funding stream that began in 2018 after the deadly Parkland, Florida, high school shooting.

The influx of money has paid for a broad array of new technology across Georgia: weapons detectors and vape sensors, instant background checks for visitors and panic buttons for teachers.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reviewed spending records from 22 districts across Georgia to see how the state security grants were being used in schools from the mountains to the coast, in districts big and small.

The records, obtained in response to a series of open records requests, list experiments with new tech like license plate readers alongside investments in long-established safety measures like surveillance cameras, door locks and the hiring of school police.

And in some cases, the new products have become the status quo.

Take the panic buttons made by Atlanta-based Centegix, which markets an alert system to announce lockdowns the way fire alarms announce an evacuation.

A majority of districts reached by the AJC — 13 of 22 — used state grants toward the cost of Centegix’s system, which allows teachers and staff to lockdown the school by pressing the button draped around their necks. The action announces the lockdown with lights, intercom messages and computer alerts.

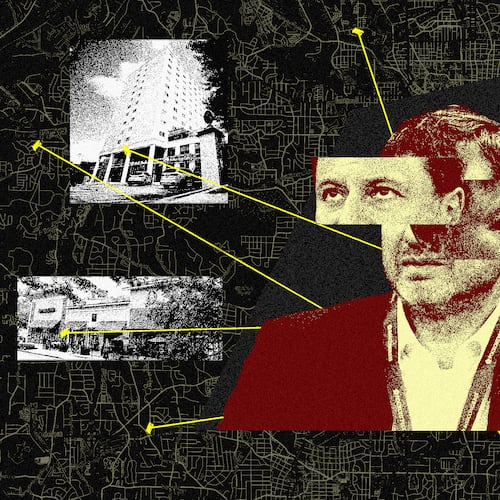

Credit: Philip Robibero/AJC; Centegix, Triton

Credit: Philip Robibero/AJC; Centegix, Triton

Centegix began work on its system after the Parkland shooting in 2018, CEO Brent Cobb said. Now, he said, its system is installed in more than 90% of Georgia schools, with badges worn by about 200,000 employees. The Legislature is requiring every school in the state to buy panic systems that can alert first responders.

Lawmakers are also requiring schools to produce digital maps so first responders can quickly navigate the halls; Centegix offers that service, too.

Otherwise, the state has given local districts wide latitude as they sort through the myriad companies selling products they hope will become schools’ new normal.

Running the state’s largest school district, officials in Gwinnett hear from lots of companies. Eric Thigpen, the county’s director of academic support, said the district gives many of them a test run.

Gwinnett has tried installing new door-locking systems and requiring clear backpacks for students, he said. It has piloted license plate readers that can flag when a suspended student drives on campus, weapons detectors using artificial intelligence to tell the difference between guns and normal belongings and vape detectors with hidden microphones.

Credit: Philip Robibero/AJC; Evolv Express, Flock Safety

Credit: Philip Robibero/AJC; Evolv Express, Flock Safety

“The list just goes on and on and on,” Thigpen said.

Evolv weapons detectors made the cut for a full rollout, he said: Gwinnett is using the grant money to put them in every middle and high school next year.

Even smaller districts like Chattahoochee County, a rural system southeast of Columbus, have been bombarded with sales pitches, Superintendent Kristie Brooks said.

Brooks and her staff eventually decided to start deleting the emails and screening the calls. Instead, the district had school police and the Georgia Emergency Management and Homeland Security Agency assess its security flaws. And it used grants to address them, with more surveillance cameras, better radios for school police and waiting areas that let staff decide who to buzz in.

“If we haven’t identified something as a vulnerability, we’re just not chasing it,” Brooks said.

On the coast, students in Savannah-Chatham County schools walk through AI-powered weapons detectors on the way to class each day. Visitors sign in on a Raptor Technologies system that runs their name through the national sex offender database.

Inside, Halo vape detectors monitor more than what’s in the air: The sensors listen for loud sounds and disturbances like fights, and they track how crowded an area gets.

There’s now enough technology to manage in Savannah-Chatham schools that the district decided it needed someone to monitor it full time, said Lt. Justin Pratt, its police department’s emergency manager. So the district this year used grant money to hire safety officers for every school. They walk the halls, check that doors aren’t propped open and staff the entrance.

In that respect, Savannah-Chatham schools aren’t unique. Georgia changed the rules for its school security grants this year, allowing districts to hire security personnel. Gov. Brian Kemp has said lawmakers wanted the funding to put a police officer in every school, although the state didn’t mandate it.

Eleven of the districts surveyed by the AJC have used the money for extra security staff.

Chattahoochee, for instance, now has a school resource officer for each of its three schools. Having someone walk the grounds with safety in mind has helped administrators juggle other tasks, Brooks said.

And over the next four years, Gwinnett is working to get officers in each of its 142 schools, Thigpen said. The district decided that although technology can supplement its staff’s capability, there’s no substitute for having an adult present, he added.

And if Gwinnett’s students are going to walk through weapons detectors, he said, someone’s got to watch them.

Stephanie Lamm, AJC data journalist, contributed to this story.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured