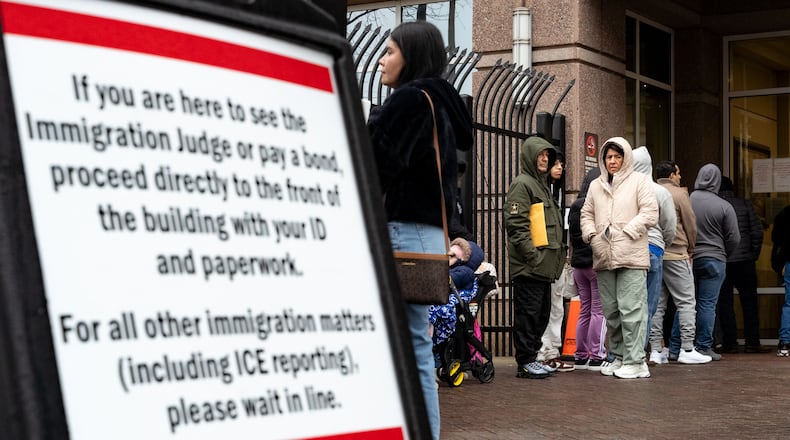

It’s a bitterly cold Tuesday morning in downtown Atlanta and dozens of people are lined up in the dark along the fence outside a federal building on Ted Turner Drive during heavy rain showers.

A woman in a long black puffer jacket walks the line, speaking in Spanish to those waiting for the building to open at 8 a.m. She offers for sale plastic rain ponchos and cups of hot coffee in large plastic foam cups.

A tall woman joins the line, carrying a blanket-covered baby carrier. She’s followed by a young woman holding the hand of a small child, a folded blanket tucked under her arm.

Some of the people have been waiting around an hour to get inside. A small group gathers under an umbrella to take photos on a cellphone, their smiles and chatter standing out amid the mostly somber expressions.

The building houses one of two federal immigration courts in Atlanta, as well as a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement office. Just around the corner is the well-known strip club Magic City and a Greyhound bus station.

Credit: John Spink / John.Spink@ajc.com

Credit: John Spink / John.Spink@ajc.com

Shortly after 8 a.m., an ICE agent makes his way down the line, giving brief instructions to those who have been summoned to the agency’s office. He offers a smile to a young man and asks if he’s in the line for the first time. Those attending immigration court hearings are directed to the security guards on the other side of the closed doors.

It’s the start of a typical day for the locals working to enforce federal immigration laws and those accused of breaking them.

President Donald Trump’s promised immigration crackdown began taking shape immediately upon his return to office, as he ushered in a spate of policy changes through executive orders that aim to put the United States out of reach for many aspiring immigrants worldwide.

After ICE arrests in Atlanta and other parts of the state, local immigration lawyers said they started noticing more immigration court cases involving detained noncitizens. They say Trump’s efforts will add to the immigration court backlog.

Seeking ‘a better future’

Many of the people whose deportation cases were called before Judge Sheila Gallow that recent Tuesday morning were teenagers. Gallow is one of the local immigration judges who handles juvenile cases. She heard from citizens of Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua and Guatemala, who live all over North Georgia.

Speaking through a court interpreter, they answered Gallow’s questions about their living situations and shared details of their journeys to America.

Unlike in much of the judicial system, immigration court officials don’t make the names and case details of people in deportation cases publicly available, which is why The Atlanta Journal-Constitution is not naming them. Federal law and regulation, including parts of the United States Code and the Code of Federal Regulations, provides certain confidentiality protections to those with immigration court cases.

Immigration courts, which are civil — and not criminal — in nature, are also subject to the Federal Records Act, the Freedom of Information Act and the Privacy Act.

A young Honduran woman told the judge she entered the United States without authorization in Texas in April 2024, when she was 17. She said her mother was dead and she did not know where her father was. She said she left her grandparents in Honduras so she could live with her sister in America, where she hoped for “a better future.”

An unaccompanied 15-year-old boy from Guatemala said he had taken a taxi to the court from Norcross, where he lived with his grandmother and uncle. The boy said his grandmother was sick, his uncle was working and he had not been able to get a lawyer.

A 16-year-old Honduran said he had entered the United States in November and was afraid to return to his home country, where his parents remain. A 19-year-old Mexican also said he feared returning home, where he would be harmed. He said he lived with his sister and brother-in-law, having entered America without any supporting documentation in November 2023 in Texas.

A mother from Nicaragua who has lived in America since 2019 spoke on behalf of her 14-year-old son, who was accused of entering the United States illegally in 2021. She said he entered with his father, whose whereabouts she does not know.

As the mother told the judge she would like to apply for asylum for her 14-year-old son, the toddler she’d brought into the hearing wandered from the wooden benches in the back of the courtroom to where she and the older boy sat. Smiling, the judge told her the toddler was “very cute” before moving on.

The odds are stacked

Gallow explained to several people whose cases had just begun that immigration court proceedings essentially have two parts. She said judges first have to determine if a person accused of violating immigration law is “removable” from the country. Judges must then consider whether the person is eligible to stay in America through any of the forms of relief available.

Most of the people appearing before Gallow that morning were relying on asylum or a special juvenile visa to avoid deportation.

Asylum is a humanitarian protection for people who can prove they are at risk of persecution in their home country. It is not easy to get, even when there is a valid basis for a person’s fear, such as death threats by violent gang members, said Atlanta immigration attorney Eddie Lopez-Lugo.

“Most people don’t qualify for it,” he said. “It’s just a very hard situation because a lot of people flee for legitimate reasons, but sadly, the law doesn’t offer protection to every single person who has a legitimate fear.”

Federal data compiled by Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse show about 35% of asylum applications are granted.

Lopez-Lugo said many adults who end up in immigration court don’t have any option other than to apply for asylum, as they’re not eligible for other relief.

There are about 3.7 million active pending immigration court cases nationwide according to the Executive Office for Immigration Review, a part of the Department of Justice that oversees immigration cases.

The EOIR’s recent data compiled by TRAC show there are about 146,000 pending cases in Georgia.

The state’s immigration judges used to have a reputation for being among the toughest in the country, but a lot has changed in the last five years, including many of the judges, said Atlanta immigration lawyer and adjunct professor Charles Kuck.

“The courts today are much more fair than they have ever been,” he said. “We want a court that’s just. And I think we’re pretty close to that in Atlanta.”

Immigration court judges are appointed by the attorney general as employees of the DOJ and have historically been sourced from the Department of Homeland Security. In recent years, the bench has diversified with lawyers from private practice and nonprofits who bring different perspectives, Lopez-Lugo said.

“There are still some judges that are denying a lot of the cases, most of them, over 90%,” he said. “There’s a few judges who are more generous and grant a higher number of cases. It also depends on the country you’re from. That really affects who wins and who doesn’t.”

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

In fiscal year 2024, countries whose citizens had the lowest asylum grant rates included Dominican Republic, Mexico, Colombia and Brazil, TRAC reports. Asylum-seekers from Belarus, Afghanistan, Uganda, Eritrea and Russia had the highest rates of success.

Atlanta’s other immigration court location is at the corner of West Peachtree Street and Ivan Allen Jr. Boulevard in the Peachtree Summit Federal Building. There is a third immigration court in Georgia, at the Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin.

The latest EOIR data on case outcomes nationwide show removal in more than 86,000 cases in fiscal year 2025, while relief from deportation was granted in about 10,000 cases.

Removal can be a slow process

Because of the immigration court backlog, it typically takes years for cases to be resolved, said Emily Davis, an Atlanta immigration lawyer and adjunct professor. She said cases of detained noncitizens tend to move faster as there are fewer of them and they take priority.

Lopez-Lugo said he gave consultations in 2024 to clients whose first hearing is in 2027. And the caseloads are increasing for judges presiding over detained noncitizens, with Trump’s recent efforts to arrest thousands of people on ICE’s radar, he said.

Asylum-seekers can get work permits while they wait for a decision.

Many of the people who recently appeared before Gallow had their cases postponed several months so they could get help from an attorney. Gallow provided them lists of local immigration lawyers, including those who offer free or low-cost services.

Unlike criminal defendants, people fighting deportation are not entitled to an attorney. Many represent themselves, often supported by relatives or friends.

About 32% of people with immigration court cases are represented by an attorney, the EOIR reports.

Each case begins when the Department of Homeland Security issues a notice to appear in immigration court, listing an alleged violation of immigration law, such as entering the country without authorization.

In preliminary hearings that happen daily in immigration courtrooms, dozens of people are called before a judge to explain one by one how their cases are progressing. Ultimately, they are asked whether they admit or deny the allegations against them and if they are seeking relief from deportation.

In a final hearing, an immigration judge decides whether a person should be granted relief or deported.

Appeals of immigration court decisions go to the EOIR’s Board of Immigration Appeals. Cases can progress from there to federal appellate courts including the Atlanta-based 11th Circuit, which has jurisdiction over Georgia, Florida and Alabama.

Lopez-Lugo said appeals can add years to a case. He said some detained noncitizens choose not to appeal simply because it prolongs their detention.

There were more than 112,000 case appeals pending at the end of fiscal year 2024, the EOIR reported.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured