PLAINS — The sturdy, little wood table that Jimmy Carter built for children waits in a backroom of his church.

The former leader of the free world’s casket will go to Atlanta, to be visited by a fellow governor, and to the Carter Presidential Center, where the former president worked to solve problems around the globe. It will lie in state in the U.S. Capitol’s soaring Rotunda, where the very powerful will pay their respects. And it will travel to the National Cathedral, with its limestone walls, gargoyles and towering stained glass windows.

Then, the body of the man from Plains will finally make its last stop before the grave.

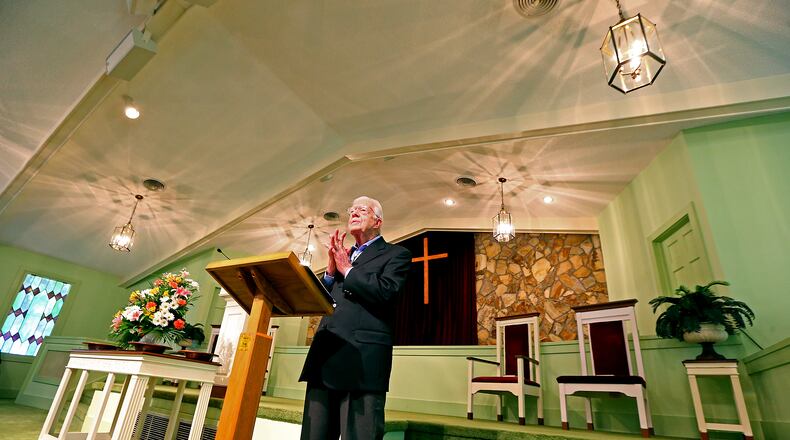

His remains will rest briefly for a private funeral Thursday at Maranatha Baptist, the little country church with pale green walls where he taught Sunday school for decades.

Tucked behind the sanctuary, in a room marked “Preschool 2&3,” the small table Carter crafted waits, ready to continue serving simple needs.

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

He designed it without any real flourishes. It was crafted for purpose, as he might have thought all of us are.

“I have one life and one chance to make it count for something,” Carter is often quoted as having said. “… My faith demands that I do whatever I can, wherever I am, whenever I can, for as long as I can with whatever I have to try to make a difference.”

Within a year of leaving the most powerful job in the world, he made the kids table, round with rich grains, for a small backroom of a one-story church in a tiny South Georgia town.

Burned into the underside of the tabletop, in small letters and numbers, he wrote “Jimmy Carter” and dated it “1-82.” Maybe his inscription was occasionally seen by children young enough not to have forgotten the joy of crawling or looking under furniture.

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Nelle Ariail hadn’t know about the signature. Not until a reporter she was touring around carefully looked under the piece that Ariail had said had been built by the former president. Ariail was surprised.

She has taught children around that table for decades. It was already in the church when she joined Maranatha in the fall of 1982, when her now-late husband became the church’s pastor, a position he held more than 20 years.

On the table built by a president, preschool students have squished her homemade versions of Play-Doh. Kindergartners and first graders leaned into it when painting or coloring with crayons. They sat around it while looking at books and listening to Bible stories and learning lessons. Most of them have grown up and moved on now.

“It was used a lot,” Ariail said in 2023. Fewer kids are regularly at the church these days, but “it still gets used some.”

It’s “easy to use with the kids. It’s nice because it is round.”

“Very sturdy,” she said. Never had to be repaired.

Carter crafted it in a way, with certain cuts and a transparent finish, that highlight the rich grain of the tree it came from. He designed it with a single pedestal support and a smaller round base. He built the tabletop from carefully selected wood expertly pieced together. Smoothed to prevent splinters. Sharp edges rounded to reduce mishaps.

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

In 2023, a reporter showed photos of the table to Alan Noel, an Atlanta area antique and wood restoration specialist who has been in the business for decades.

After some contemplation — it can be hard to do precise analysis from photos alone — he concluded the table’s maker had used the wood of an olive ash tree. The grain is remarkable, Noel said.

The table’s value? he offered unasked. “$25.” But then he was shown another photo, one with the maker’s signature.

“Oh, Jimmy Carter. Well, that bumps up the price a little bit,” he said and chuckled. “I was a big fan of his.”

Carter was a careful man with wood. He accumulated more than 100 books on woodworking. He consulted with people he considered some of the top woodworkers in the nation and the world.

“He always strove for perfection in everything he did,” said Russ Filbeck, a longtime woodworker from San Diego who visited with the Carters at their home in Plains and hosted them at his shop in California.

“It was all built to be functional. Neither of us built pieces to be art forms.”

Growing up on his family’s farm, Carter learned the basics of building, like how to erect a hog shed or replace shovel handles. While in the Navy in the 1940s, he tried to limit his expenses by building furniture for his young family. As president, he would tinker in a workshop he found at Camp David. At the presidential retreat he fashioned small gifts for loved ones.

After getting walloped in his reelection run, Carter’s staff contributed money to get him a gift as he prepared to depart the White House. They planned to buy him a Jeep, Carter would later say, but he let it be known that he really wanted woodworking equipment. The money went to a trove of tools from Sears. Carter set about building a workspace in the garage of the home he and Rosalynn shared in Plains. He later wrote, “This has turned out to be one of the best gifts of my life.”

He went on a building tear, that first year out of office. He created beds and armoires, benches, medicine cabinets and even toilet paper dispensers. Much of what he made was destined for a cabin the couple had built in North Georgia. He also was embarking on another kind of creation: making plans for his presidential library. A year or so after leaving the White House, he had the idea of the Carter Center as a site to resolve conflicts and foster peace. That must have been around the same time he was working on the kids table for his church.

Carter labored at other hobbies as a former president. He volunteered for Habitat for Humanity building homes. He made wine. He wrote lots of books. He painted, and wrote a book about it. He enveloped himself in woodworking, and wrote a book about that, too.

He liked seeing the visible proof of his work, he wrote in “The Craftsmanship of Jimmy Carter.” But there was more: “The excitement of an original design, the meticulous detail of precise measurements, the characteristics of the chosen wood, the heft and beauty of the hand tools — some of them ancient in design — are all positive aspects of crafting a piece of furniture.”

The purpose of his book, he wrote, “is to show the reader that even those with limited talent can develop adequate skills to produce worthwhile things.”

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

By his own account, Carter made more than 150 pieces of furniture, from porch swings to four-poster beds, five baby cradles for family members, chests and a hunting stool with a padded, rotating seat that he crafted in the 1950s. Not every piece was about utility. He made “love darts,” with a wooden arrow piercing a wooden heart. One is inscribed “To Rosalynn” and “Love, Jimmy.”

As he grew more skilled, he typically built without nails, instead relying on pegs and glue and carefully designed interlocking joints. Often he used wood he found on his property or that others brought by for him.

Much of the furniture went to family and friends. Carter made a shelf for Ariail to display her collection of miniature dolls. And he helped her son build a bookcase as a Christmas gift for the son’s then-teenaged daughter.

Some of the former president’s pieces were auctioned off at annual Carter Center fundraisers, going for tens of thousands and even hundreds of thousands of dollars each.

He once told an interviewer at The Wall Street Journal that he hoped a bench he made would still be in use in 500 years, with the person sitting in it knowing a president had made it.

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

On his casket’s stop at Maranatha, the man from Plains will be among his handiwork, all still serving their purposes. Where he delivered Sunday school lessons with titles such as “A Call to Hope” and “Becoming God’s People,” is the cross he fashioned from maple. The wooden offering plates he turned on a lathe carry his initials, “J.C.”

And down a hallway, in the preschool room, is the little round table, waiting to serve another generation.

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured