In all my travels around the world and across the nation, one place has drawn me back time after time: Sapelo Island on Georgia’s coast. Lying at the center of the state’s curved coastline known as the Georgia Bight, Sapelo is still isolated, reachable only by boat and still mostly wild and undeveloped.

It’s one of the most alluring places I’ve ever visited. The anticipation of going there has always kindled a sense of adventure in me. Sixteen thousand acres of sand, wide beach, maritime forest and boundless salt marsh, Sapelo is a place of superb natural splendor. Because of its unblighted landscape, it is also home to the University of Georgia’s Marine Institute, where much of the world’s groundbreaking research on coastal salt marshes took place, and still is taking place. Among marine scientists worldwide, Sapelo is sacred ground.

But Sapelo is hallowed ground for another reason. It is home to Hog Hammock, probably the most famous, most written-about Gullah-Geechee community on the entire Southeast coast. Its 40 or so current residents are descendants of former slaves who once worked the island’s big plantation. Most of the friends I once had in Hog Hamock have passed away. I stayed in their homes and swapped stories with them about growing up on a sea island (I grew up on Johns Island, S.C.) and how I, as a white man, also was immersed in the Gullah-Geechee culture. We joked about how “outsiders” could not understand our lilting patois.

So, it was with immense sadness and heartbreak that I learned of the awful tragedy that took place on Sapelo on Oct. 19. Seven people were killed and several more critically injured when the gangplank on which they were standing collapsed while they were waiting to board the ferry boat back to the mainland.

They were coming back from the annual Sapelo Island Cultural Day at Hog Hammock, a grand celebration of the rich Gullah-Geechee culture originally started by the Sapelo Island Cultural and Revitalization Society. It is a wonderful day of everything Gullah-Geechee — its songs, stories, dances, foods. They all were passed down to the present generation from their ancestors, who were brutally removed from their West African homeland, enslaved on Southern plantations and, after emancipation, endured the Jim Crow era.

Over the years, I attended a couple of the festivals, the latest one in October 2009. The events, though, have changed little since then. Their purpose remains the same, to honor the Gullah-Geechee culture and inspire new generations to save it. Even though the festivals are open to the public, I had a personal invitation to attend the one in 2009 from my old friend, Cornelia Bailey, who was the undisputed matriarch of Hog Hammock before her death in 2017 at age 72. Every time I was on Sapelo, I tried to go by Hog Hammock to see her. Every time she greeted me with a big bear hug and a sincere, “How you doing? So glad to see you” in her deep, rich voice.

Credit: AJC staff

Credit: AJC staff

In her beautiful accent, Cornelia, a born storyteller, spoke of two kinds of people on Sapelo, the “com-yas” and the “bin-yas.” Com-ya is the Geechee term for newcomers. Bin-ya — as in “been here a long time” — is Geechee for long-time residents.

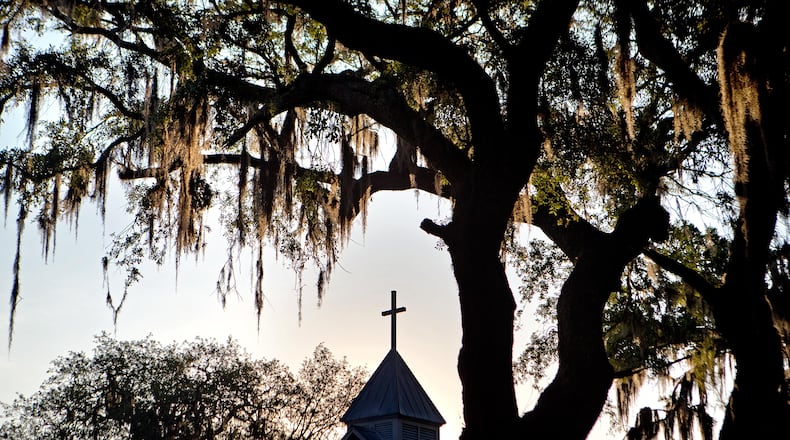

On the warm, sunny day of the 2009 festival, I strolled around the grounds with Cornelia as she talked to folks and visited booths and told story after story. Everybody knew Cornelia, who had a fierce determination to preserve her people’s traditions and customs. African-like drumming thumped above the festival goers’ incessant chatter and laughter. Huge live oaks festooned with Spanish moss provided shade. The odors of smoked mullet and other foods pervaded the air. Some men walked around in Union Army Civil War uniforms to honor, they said, the Buffalo Soldiers, the heroic African-American men who fought in the war.

Cornelia introduced me to a young man who said he was there to learn more about the Gullah-Geechee’s use of medicinal herbs, particularly a sun-loving plant that grows all over the island and folks call “life everlasting.” Most Southerners know it as “rabbit tobacco” (Gnapthalium obtusifolium). Its little leaves turn a silvery gray in late summer when it matures and is ripe for picking. Corneilia explained that the wild plant has been used extensively for centuries by Gullah-Geechee folk in the Low Country of Georgia and South Carolina as a substitute for tobacco, to treat wounds, freshen air in homes and to make a strong tea that supposedly gives one longer life.

Cornelia noted that she talked about the tea in her 2000 book “God, Dr. Buzzard and the Bolito Man” (written with Christena Bledsoe).

”You’d drink life everlasting in the evening,” she wrote. “It was the poor man’s Lipton, with its own stimulant, and it got you up and going just as good as store-bought tea.”

Interestingly, the young man noted that a similar plant in West Africa also has long been used there for the same purposes — a part of the herbal medicine lore that enslaved Africans brought with them when they were removed to America in chains.

Some other festival folks joined our conversation. One noted that life everlasting also was placed in various spots in homes to ward off evil spirits and other spooky denizens of “cunjuh,” a form of voodoo once widely practiced on the sea islands. One of the sinister spirits, Cornelia said, was the “hag,” which supposedly could “ride” you at night and suck the breath from you. In the mornings, sleepy-eyed people would complain that a hag had ridden them all night, she said.

As we walked on at the festival, we stopped at a creaky wooden table where folks were cooking and serving one of Sapelo’s best-known culinary dishes, red peas and rice. As we munched on a sample, Cornelia talked about her “Gullah Red Pea Project.” Sapelo’s peas, she said, are heirloom plants originally brought from Sierra Leone by enslaved Africans and grown on the island, where they became a staple. Before she died, Cornelia was trying to brand Sapelo Red Peas and produce them commercially as a way of helping island people make a profit and stay connected with their heritage.

At another table beneath a spreading oak, we stopped to watch a woman deftly weaving a sweetgrass basket, an icon of the Gullah-Geechee culture. The basket-making material was spread before her on the table — sweet grass stalks, pine needles, black needlerush and strips of palmetto, all harvested from the nearby woods and salt marsh. Enslaved West Africans brought their basket-making skills with them three centuries ago when they crossed the Atlantic in slave ships. In the early days of coastal settlement, sweet grass baskets were used for utilitarian purposes — winnowing rice, carrying cotton and holding laundry, sewing supplies, breads, fruits and other items. Today, the baskets are considered works of art. Scholars say the baskets are one of the most visible links between the Gullah-Geechee and their West African heritage.

Next, we strolled into Sapelo’s barn-size, wood-sided community hall painted a gleaming white. An elderly man seated in a straight-back wooden chair was knitting another Gullah-Geechee icon, a castnet. His tools were a plastic “needle” and a flat piece of wood resembling a fingernail file. With amazing dexterity, he looped and laced knot after knot of strong netting material to make what eventually would become a circular, gossamer net 8 to 12 feet wide. Small metal weights called “bullets” would be attached to the net to help it sink quickly into the water.

When a net is cast, the man explained, it quickly unfolds into a perfect circle as it descends into the water. Any creature within the circle — shrimp, mullet, crab, stingray — is trapped when the net is suddenly jerked out of the water. Countless numbers of Gullah-Geechee people over the centuries have relied on castnets to feed themselves and their families with bountiful seafood from tidal creeks and rivers that wind through the salt marsh.

The festival’s stage was next to the community hall, and we sat in folding chairs in the open air to watch singers and dancers perform generations-old Gullah-Geechee songs, dances and rituals that clearly had an African influence. First was a group of women, dressed in dazzling, colorful, full-length dresses, who performed several traditional dances from their ancestral homes in West Africa. Then came the ring shouters. In a ring shout, participants shout, stomp and shuffle counterclockwise in an energetic, hypnotic manner, all the while engaging in call-and-response singing and vigorous hand clapping. A stick beating on the wooden floor provides a mesmerizing, drumlike rhythm. The ring shout was long a part of many Gullah-Geechee Christian services on the sea islands. A shout could go on for hours to the point of exhaustion, leaving a participant sprawled on the floor in what was said to be a state of religious ecstasy.

The day was topped off by singers who performed as their enslaved ancestors once did — a capella with only the accompaniment of rhythm instruments such as the tambourine and jimbay drum. (Musical instruments were forbidden among enslaved people.) With their enthusiastic performance, the singers were playing an important role in preserving Gullah-Geechee spirituals and songs, Cornelia told me.

Finally, as the festival wound down, I told Cornelia how glad I was that I had attended and hoped that the wonderful Gullah-Geechee culture will thrive forever. In my mind, if the Gullah-Geechee cuture dies, the very soul of the Georgia and South Carolina sea islands dies with it. African Americans will lose their purest link to the past.

“Yes,” said Cornelia. “But I fear for the survival of my culture and my people on this island.”

Credit: David Goldman

Credit: David Goldman

About the Author