Joseph Blaylock made the news in 1960 for accomplishing something remarkable.

Piloting a U.S. Air Force jet tanker, he transported home fellow service members on a 7,175-mile, nonstop trip from Japan to the United States. Blaylock finished the grueling flight in 12 hours and 32 minutes, with barely any rest. His flight lasted only four minutes longer than a 7,000-mile trip Gen. Curtis LeMay completed between the same countries two years earlier, according to news reports.

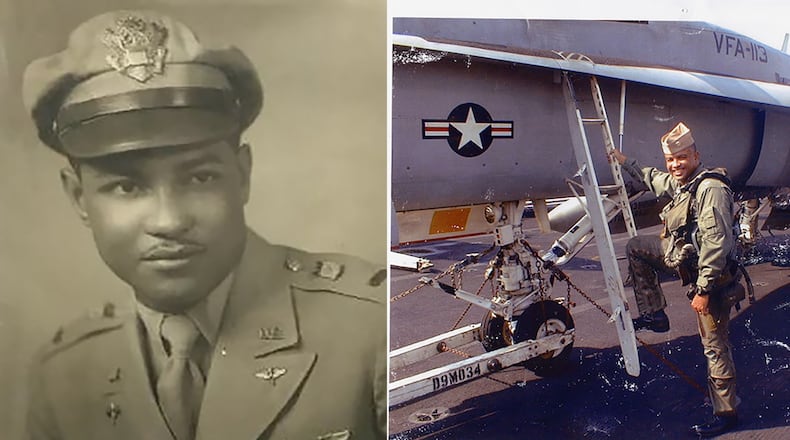

Even more remarkable is what Blaylock did years before that achievement. A Georgia native, he was among the famed Tuskegee Airmen who helped pave the way amid World War II for the desegregation of the U.S. military.

At a Veterans Day event in Riverdale on Monday, Blaylock’s son, Harvey McDonald, will speak about carrying on the legacy of his father and other pioneering Black pilots. McDonald knows something about that, as he blazed his own trail as a U.S. Navy aviator.

“I am here because of them, and so are a lot of us,” said McDonald, who will speak at the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Georgia as part of an event organized by the Atlanta Chapter Tuskegee Airmen. “Without the Tuskegee Airmen, none of us would be in aviation.”

Credit: Photo Courtesy of Harvey McDonald

Credit: Photo Courtesy of Harvey McDonald

‘Cool, confident, competent’

The youngest of 14 children, Blaylock was born on the outskirts of Albany, in South Georgia. He attended Albany State College for six months before joining the military in 1944 during WWII. Blaylock completed aviation training at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. From 1941 to 1946, about 1,000 Black pilots were trained as part of the program.

Nicknamed “Red Tails” because of their fighter planes’ painted tails, Tuskegee Airmen flew more than 15,000 sorties during the war. Sixty-six of them died in combat. In all, according to the National WWII Museum, the Tuskegee Airmen earned eight Purple Hearts, 14 Bronze Star Medals, three Distinguished Unit Citations and 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses.

By 1945, more than 1.2 million Black men and women were serving in the military.

Blaylock did not get a chance to fly against the enemy in Europe before WWII ended that year. After he was discharged from the military in 1947, Blaylock settled in Atlanta and worked as a railway mail clerk while attending Morehouse College. Recalled to active duty in 1952, he flew combat missions during the Korean War, said Bill Patterson, president of the Atlanta Chapter Tuskegee Airmen. He also flew a refueling tanker over Vietnam during the Vietnam War, according to his son, and he served with U.S. Strategic Air Command during the Cold War.

Phil Goulding, a reporter for The Plain Dealer newspaper in Cleveland, was among the 41 people aboard Blaylock’s jet tanker when he made his 1960 flight from Yokota Air Base, Japan, to an air base in North Carolina. In his report, Goulding described Blaylock, then a captain, as “cool, confident, competent after more than 10 hours in the seat of the aircraft commander. He has not left it for more than 45 seconds, total.”

“In his native Georgia, the white-sheeted hoodlums of the Ku Klux Klan would attempt to deny him the right of an American,” wrote Goulding, a U.S. Navy veteran who would later become a Pentagon spokesman during the Vietnam War. Goulding added that Blaylock’s flight crew was “trained to perfection.”

Blaylock reached the rank of lieutenant colonel before retiring from the military. Later, he worked as security specialist for the Federal Aviation Administration and assisted in forming the Atlanta Chapter Tuskegee Airmen, which was incorporated in 1976.

“He helped guide us and kind of gave us the foundation of where we are right now,” Patterson said of the chapter.

Blaylock died in 1994 at 68.

Credit: Photo courtesy of Harvey McDonald

Credit: Photo courtesy of Harvey McDonald

Morehouse men

Like his father, McDonald grew up in Georgia and attended Morehouse College. Blaylock remained in McDonald’s life after divorcing his mother. McDonald remembered him as fun-loving and charismatic.

“Everybody knew him by ‘Joe,’” McDonald said. “Even under pressure, he could always give a laugh … and get you through it. At the same time, he was a no-nonsense perfectionist in making things happen.”

McDonald said his father became upset when he told him he had decided to join the Navy. Amid racial tensions in October of 1972, a riot broke out between Black and white sailors aboard the USS Kitty Hawk aircraft carrier as it was deployed to the South China Sea. Many sailors were injured.

“He was afraid for me. He said, ‘Man, don’t you know they are rioting and stuff, and you will be the only Black guy on the ship, and you might get lynched?’” McDonald recalled. He remembers responding: “Well, Dad, you guys were almost getting lynched in Tuskegee and other places. ... I feel this is my purpose.”

McDonald thrived in the military, becoming the nation’s first Black aviator selected to command an all-weather, medium-attack squadron flying the A-6E Intruder and to command an aircraft carrier air wing, according to the National Naval Aviation Museum. He retired from the Navy in 2004 after serving 32 years.

For McDonald, Veterans Day is meant to recognize the sacrifices U.S. service members make, including the time they spend away from their families. He said his stepfather and brothers also served in uniform.

“There is a kinship among those who have served. There is respect,” said McDonald, who lives in the San Diego area and teaches mathematics at National University. “We look each other in the eye. And no matter which branch of service we are in, you know you gave up something for something much larger.”

Not long before his father died, McDonald invited him onto the deck of an aircraft carrier for a day so he could attempt to “scare him.” His father remembered marveling at the “crazy people” he saw making precarious landings on carriers during the Vietnam War. As the two explored the carrier that day, McDonald said, his father joked about Navy pilots: “Oh, my God, for you to do this, you either have got to be the bravest guy or the stupidest guy in the world.”

“He had tears in his eyes,” McDonald said. “And we hugged each other.”

Credit: Photo Courtesy of Harvey McDonald

Credit: Photo Courtesy of Harvey McDonald

About the Author