An intellectually disabled Georgia man inexplicably sat on death row for more than three decades waiting on a court to hear his case, despite state and federal rulings saying it is illegal to execute those who don’t have their full intellectual capacities.

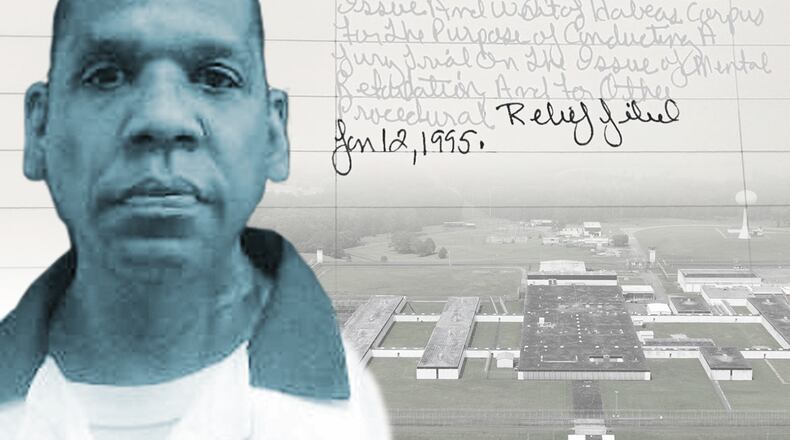

Dallas Bernard Holiday, of Wrens in Jefferson County, was convicted of the 1986 killing and robbery of a senior citizen who was out on his daily walk. His lawyers, in court filings, have said that Holiday reads on or at a third grade level and has a low IQ, scoring 69 and 70 on separate exams. Anything 70 or below is considered intellectually disabled in the court’s eyes.

In 2022, Holiday’s situation was finally brought to the attention of a judge who agreed to consider the case, which had been dormant since 1990, court records show. He was resentenced last year to life, and moved to a state prison just outside Augusta.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution learned of his resentencing last year as reporters reviewed state records for those facing the death penalty in Georgia.

“The system failed everybody here. It failed Mr. Holiday. It failed the family of the victim,” Jefferson County District Attorney Tripp Fitzner told the AJC in a phone interview. “Short of a time machine where we can go back and fix whatever happened back then, nobody should come away from this happy.”

While reporting on Holiday’s case, the AJC also identified a second death row inmate, Michael Miller, who also has low IQ scores and spent decades waiting on a court-ordered proceeding to determine whether he is intellectually disabled and should not be executed.

His lawyers filed reports from experts years ago stating his IQ is 60, 61 or 69, depending on the test given, and too low for him to be put to death for the killing of a Walton County man. No action has been taken or court filings made in his case in 15 years, and Miller, of Atlanta, remains on death row at the state prison in Jackson, the AJC found.

The lengthy delays in the two cases raise questions about how vigorously Georgia’s criminal justice system has sought to defend or resolve the cases of people who are poor and intellectually disabled who have been sentenced to die at the hands of the state.

The two cases represent “a consequence of Georgia penny-pinching” to pay defense attorneys beyond the initial stages of appeals for indigent individuals on death row, said B. Michael Mears, a professor at Atlanta’s John Marshall Law School.

Mears, who as a lawyer defended more than 150 people facing death sentences in Georgia’s courts, said it is highly unusual the two inmates’ cases were allowed to sit so long without any action by the state’s criminal justice system.

Both Holiday and Miller were convicted of murder in the late 1980s, when Georgia had roughly three times as many inmates under death sentences as it does now. At the beginning of 1988, the year Miller was sentenced to death, the state had 102 people on death row. Today that number is down to 33 men and one woman.

‘Crushing workload’

The U.S. Supreme Court in 2002 declared it unconstitutional in all 50 states for intellectually disabled inmates to be executed. The high court said doing so is a violation of the Eighth Amendment prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. The court opined that executing the intellectually disabled does not serve the purposes of deterrence and retribution often used to justify the death penalty. The court also noted that intellectually disabled individuals faced a higher risk of wrongful execution and “may be less able to give meaningful assistance to their counsel.”

That ruling came 13 years after Georgia’s highest court had already reached a similar conclusion. Not long after Holiday and Miller arrived on death row, the Georgia Supreme Court in 1989 ruled it unconstitutional in Georgia to execute people who are intellectually disabled. The ruling came in the case of Son Fleming, who had been convicted of killing the police chief of a tiny South Georgia town in 1976.

The Fleming decision was retroactive. It meant juries needed to be convened and special trials held to determine whether those already on death row were intellectually disabled beyond a reasonable doubt. In at least 19 cases, attorneys for men on death row called for such a trial, state records show. Both Holiday and Miller were among those for whom courts ordered that step.

Under Georgia law, those trials need to be held in the counties of original conviction. For Holiday, that was Jefferson County, roughly an hour’s drive southwest of Augusta. For Miller, that is Walton County, about an hour’s drive east of Atlanta.

Those county courts are where both Holiday and Miller’s cases appear to have stalled, court documents reviewed by the AJC revealed.

There’s no sign the 1990 judge’s order sending Holiday’s appeal back to Jefferson County ever arrived at the county court clerk’s office, a judge there wrote in Holiday’s resentencing order last year. That left court officials unaware they had been ordered to hold a “Fleming trial” for Holiday, court records show.

Meanwhile, the court order remanding Miller’s appeal did arrive successfully in Walton County. But other issues got in the way, records show.

In the first few years Miller was on death row, the small nonprofit that represented him and Holiday, the Georgia Appellate Practice and Educational Resource Center, was struggling to survive amid years of manpower and staffing challenges.

Court records and press accounts paint a desperate picture at the center. The small staff operated on a shoestring budget and struggled financially.

“I have had a crushing workload over the last six months,” Tom Dunn, the center’s then-executive director, said in a 2000 court hearing for Miller, according to a Walton County transcript.

Credit: Georgia Department of Correction

Credit: Georgia Department of Correction

Several years later, Dunn would tell the press the heavy workload had hurt his health and he eventually left the nonprofit.

His successor, Brian Kammer, would later tell the court that the center could no longer represent Miller. It didn’t have the manpower or expertise to handle Fleming trials, he wrote in a 2009 letter.

“If a mental retardation trial is unavoidable, I will help to find qualified and competent attorneys to represent Mr. Miller in that proceeding,” Kammer’s letter said. That was the last entry in Miller’s file reviewed by the AJC.

‘Get this matter taken care of’

It’s unclear what caused Holiday’s case to resurface when it did in 2022.

During a hearing that year, the judge handling Holiday’s case apologized to him for it being “off track so long” and vowed to address what amounted to a three-decade delay in his appeal.

“Right, right,” Holiday responded, according to the hearing transcript.

“Thirty-three years,” the judge said. “So I want to make sure that we get this matter taken care of.”

Fitzner had been an assistant district attorney in the circuit for years before he was elected to be DA in 2020. He told the AJC he had never heard about the case and wasn’t aware of Holiday’s situation until he received a call a couple years later from Anna Arceneaux, the current executive director of Georgia Resource Center, which still represents many of Georgia’s indigent death row inmates today.

“This was a terrible situation. It was a terrible miscarriage of justice across the board,” Fitzner said.

Arceneaux, who has been at the center since 2019, declined to comment for this story.

Fitzner’s office, along with Arceneaux, reached a settlement for Holiday’s sentence to be commuted to life, and his appeals to be halted. The DA said that was the only practical way to conclude the case after decades of delays. Holiday, who turns 63 this year, is now housed at Augusta State Medical Prison.

Meanwhile, Miller is still awaiting resolution for his case.

How much longer Miller will have to wait on his IQ determination is not clear. The current district attorney for the Alcovy Judicial Circuit, which covers Walton and Newton counties, Randy McGinley, did not return emails, phone calls, voicemails or letters sent to his offices by an AJC reporter seeking comment on Miller’s case.

McGinley has been the DA since 2020 but has been working in that office since 2011, two years after the last action in Miller’s Walton County appeal.

Digital Audience Specialist Mandi Albright contributed to this story.

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured