On Tuesday, former President Jimmy Carter will turn 100 years old. I have known and worked with him for more than half his lifetime and have boundless admiration for his determination to do right in the world.

It is a cause for reflection that Carter’s long life — he will be the first president in U.S. history to reach the century mark — has spanned a remarkable period of American history, with events that shaped his life and that he helped shape. These include the Great Depression, the New Deal, the Great Society and profound economic, racial and political movements.

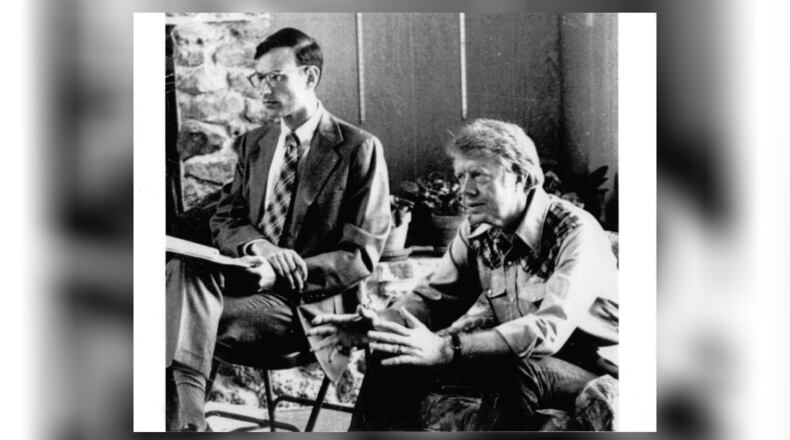

Handout

Handout

The United States of America of 1924 into which Jimmy Carter was born was very different from the country in which we live today. Especially in rural agricultural communities, he and other Americans lived without what we consider the bare necessities of everyday life, including electricity and indoor plumbing.

Carter’s father was a county director for the Rural Electrification Administration (part of the New Deal), and the president recalled the day electricity came to Plains, Georgia, as one of the most transformative events of his own life, bringing his first indoor shower. But witnessing the hardships of the Depression on rural America, with depressed farm prices and poor people foraging for food, had a lasting impact on his belief that government should play a role in helping the disadvantaged.

The most important domestic issue that links 1924 and 2024 is race, and here Carter’s path on civil rights mirrored that of the South and much of the country.

As a child, his closest playmates were Black, and he spent many nights at the home of a Black couple, Jack and Rachel Clark, who worked at the Carter family farm. But as he entered political life in Georgia, he was cautious about not getting too far in front in condemning racial discrimination. Still, he pushed for his church to admit Black parishioners and refused to join the local White Citizens Council, at risk to his peanut business.

In his successful 1970 gubernatorial campaign, he appealed to white segregationist voters on a class basis, with no hint he would fight racial discrimination, while also seeking support from Martin Luther “Daddy” King Sr. At his inauguration as governor, to the dismay of his conservative supporters, he boldly declared, “The time for racial discrimination is over.” He then appointed Black people for the first time to major positions in his administration.

As president later in the decade, he appointed more Black, Hispanic, Jewish and female people to federal judicial posts and senior executive branch positions than all his predecessors combined. He supported affirmative action in university admissions, which lasted for more than 40 years before being barred by the conservative Supreme Court.

For liberal Democrats looking for an expansion of the Great Society, he offered instead tight budgets; support for education for low-income students; created about 10 million jobs; deregulation of all forms of transportation, crude oil and natural gas; major post-Watergate ethics laws still on the books; and a sterling environmental record that doubled the size of our national parks and provided the first incentives for clean alternate energy, with solar panels for the White House.

Abroad, Carter’s life has seen multiple wars — from World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Yugoslav, Iraq and Afghanistan to today’s conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza — many of which have involved the United States as a combatant, supporter or mediator. Though Carter did not fight in any of these wars himself, he was a military man, graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy and serving as a nuclear submarine officer during the early years of the Cold War. His experience shaped his views regarding the use of military force, making him skeptical of the utility of nuclear weapons and seeking means other than war to advance American interests.

As president, he negotiated the SALT II nuclear arms control treaty that, though never ratified by the Senate, was honored by the United States and the Soviet Union (and later Russia) for decades. At the same time, he recognized the need to reverse the post-Vietnam decline in military spending. All the major weapons systems for which Ronald Reagan is credited — the cruise missile, MX mobile missile, stealth bomber, intermediate nuclear weapons in Europe — were begun by Carter, a buildup that helped win the Cold War.

Handout

Handout

His experience regarding war also pushed Carter to his greatest achievements as a peacemaker, receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002. The Camp David Accords and the subsequent Egypt-Israel peace treaty represent the most important diplomatic accomplishment by an American president in U.S. history. Over 13 days and nights of tireless, brilliant diplomacy, he developed creative solutions to bridge political and personal differences, crafting a peace agreement that has lasted to this day, unshaken even by the current fighting in Gaza. I believe that if Carter had been reelected in 1980, he would have built on the Camp David Accords to reach a resolution to the Palestinian issue.

After leaving the White House, through his work at the Carter Center, he has remained a major international figure, negotiating a cease-fire during the Bosnian war, brokering a deal to restore democracy in Haiti, monitoring more than 100 elections around the world, working to eradicate Guinea worm and river blindness in Africa and promoting human rights.

Carter’s 100 years have also seen the rise of new geopolitical power centers, most notably China and Iran, and he was president during crucial moments marking the emergence of both nations in the late 1970s.

With China, Carter built on the initiative of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger, establishing formal diplomatic relations with Beijing while creating a new relationship with Taiwan through the Taiwan Relations Act. The act provided arms to enable the Taiwanese to protect themselves, a relationship that endures to this day.

Carter’s accomplishment made it possible for China to rejoin the global economy and become a major U.S. trading partner, even as China and the United States have now become strategic competitors. Still, these economic bonds have helped to temper the geopolitical conflict between the two countries.

With Iran, it was on Carter’s watch that the Shah of Iran fell and the radical Islamic Revolution began, punctuated by the humiliating hostage crisis that lasted for 444 days and cost him his presidency. Today, Iran and its proxies are one of the greatest national security threats to the United States, Israel and a stable Middle East.

Carter is often blamed for this outcome; but the shah lost Iran, not Carter. He was a staunch supporter of the shah’s regime against the Islamic demonstrators, and he made strong efforts to prevent Ayatollah Khomeini from coming to power and to undermine Khomeini’s regime after the revolution.

Finally, many of the most significant U.S. political trends of recent decades began during Carter’s presidency and remain potent today.

His long life span saw the emergence of the Christian evangelical movement as a major political force within the Republican Party. The evangelicals turned against Carter, the most religious man ever to be president.

Carter also saw the rise of supply-side economics, which has helped to create the massive deficits and income inequality we see today, far exceeding that of the 1970s.

For those concerned about the return of high inflation in the 2020s, it’s worth remembering that when Carter faced a more unforgiving inflationary environment during his presidency, he made the courageous decision to appoint Paul Volcker as chairman of the Federal Reserve, knowing full well that Volcker would use high interest rates to break the back of inflation, painful in the short run but reaping lasting dividends for decades.

As America marks Jimmy Carter’s centennial birthday, his impact on our country and our world far exceeded his four years in office. It was truly epoch-defining.

Stuart E. Eizenstat, who grew up in Atlanta and attended its public schools, was Jimmy Carter’s chief White House domestic affairs adviser. He served in the Clinton Administration as ambassador to the European Union from 1993 to 1996, undersecretary of Commerce for International Trade from 1996 to 1997, undersecretary of State for Economic, Business, and Agricultural Affairs from 1997 to 1999, and deputy secretary of the Treasury from 1999 to 2001. He has been Special Adviser on Holocaust Issues since 1993 in Democratic and Republican administrations.

About the Author