How much does social media influence elections and voting? I organized a team to find out.

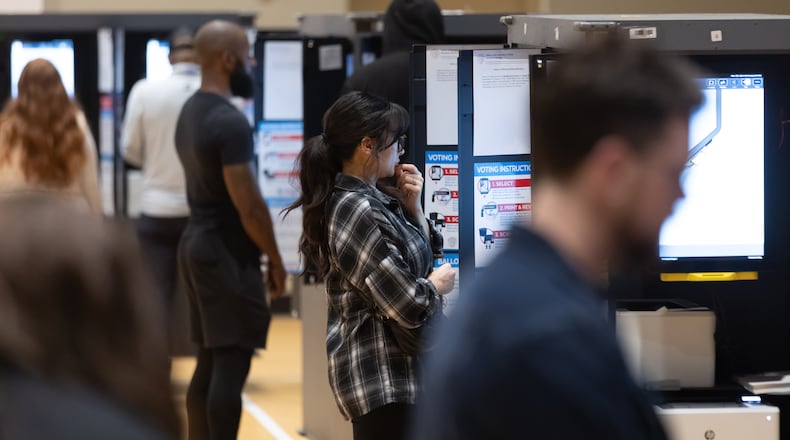

On the day of and the days surrounding last month’s election, from Nov. 4-6, a team of 60 social media monitors assembled on the Georgia Tech campus to track and respond to online issues that could negatively affect the Fulton County election. The goal was to identify material that risked disenfranchising voters, endangered people in the community or restricted the free flow of accurate political information.

The team included Georgia Tech students along with community members recruited by our partner, social impact consultancy The BLK+Cross. It was managed by Amanda Meng, a research faculty member in Georgia Tech’s School of Computer Science.

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

Our team read nearly 30,000 carefully curated posts downloaded from X, Facebook, Truth Social, Instagram and TikTok. An artificial intelligence system created by Georgia Tech students helped classify and respond to the very high volume of online material. Team members reviewed the content using a social media tracking tool that has been under development by my team over the past decade.

From this collection of social media posts, we created 187 incidents arising from serious material we felt deserved fact-checking and response. Thirty incidents were escalated to our field community partners, independent nonpartisan election observers and other stakeholders who could take positive action.

My takeaway from this experience: Online political discourse that centered on Fulton County elections was a cesspool of lies and hate negatively impacting our politics and community.

The incidents we identified and escalated were often things that are now familiar to Fulton County voters, though we were, at times, first to flag the concerns. For instance, we spent a lot of time tracking complaints from poll observers who were initially denied access to election offices during the extended absentee ballot drop-off period. On election day, we were busy with multiple made-up bomb threats menacing polling locations.

Sadly, to track and escalate these meaningful incidents, our team had to wade through an overwhelming quantity of online posts promoting hate and lies.

To demonstrate the shabby state of our online political discourse, I recently read through 50 posts randomly selected from the content we monitored. They included a lot of disproved claims about the 2020 election — “Fulton County has 300,000 missing ballots” — and the current election — “(fraudulently marked ballots) still in boxes in some van in Fulton County.” There was plenty of vitriol toward the county generally — “Fulton County is a stain on the map of this great country” or “Fulton County had been a hotbed of evil greed since the days of the carpetbaggers!” And we found hostility directed against our elected officials — “Fani Willis should resign and start preparing for the full force of the law to come down on her” — along with the occasional racist remark against county residents that I will not quote here.

A particularly unpleasant and unfortunately representative post was an online video on X featuring a man claiming to have moved from Haiti to the United States with several Georgia driver’s licenses that he used to vote in multiple counties across the state, including in Fulton County. The Georgia secretary of state called the video “an example of targeted disinformation we’ve seen this election.”

Uncritically consuming this array of hate and disinformation can lead to bad decision-making at the ballot box. In computer science, we put it this way: “Garbage in, garbage out.”

So what can be done?

First, social media platforms must improve their algorithms and moderation, though free speech principles mean we will never thoroughly sanitize our online political discourse. In addition, we all must strengthen our media literacy: our ability to select trusted information sources online, advocate against those circulating disinformation and hateful content and inoculate ourselves against such content we receive nonetheless.

At Georgia Tech, we are researching social and technical methods to enhance our media capacities and improve our social media platforms. At the same time, with The BLK+Cross and other partners, we continue to develop literacy-building programs and storytelling methods that help us better understand our local communities and boost camaraderie, even when we might disagree politically.

Thoughtful use of social media — both posting and reading — can help us have an informed citizenry, which is sorely needed for a functioning democracy.

Michael L. Best is professor of international affairs and interactive computing and executive director of the Institute for People and Technology at Georgia Tech. He has worked globally on election monitoring for more than 15 years.

About the Author