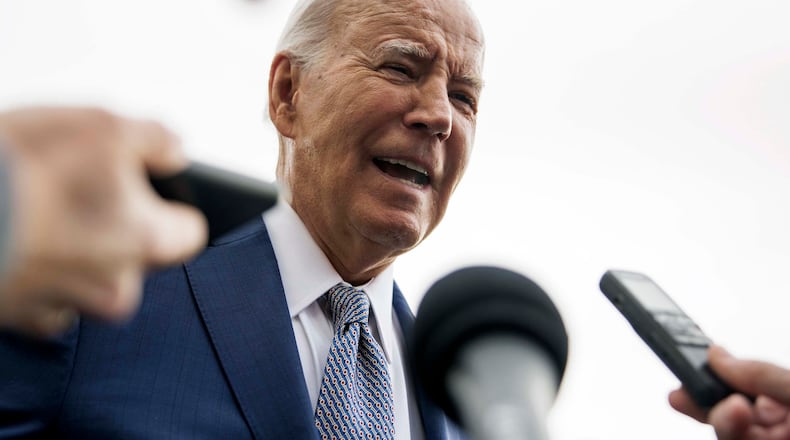

Two days before New Hampshire’s presidential primary this year, Granite State voters received robocalls from President Joe Biden suggesting they not bother casting ballots until the November election. Except it wasn’t Biden.

The calls were created with voice-cloning artificial intelligence, according to the Federal Communications Commission, which has accused a political consultant Steven Kramer of masterminding them. Last month, the commission fined Kramer $6 million. He has also been indicted in New Hampshire on state charges of felony voter suppression and misdemeanor impersonation of a candidate.

Kramer, who has pleaded not guilty, told The Associated Press he was trying to send a wake-up call about the potential dangers of artificial intelligence, not influence the primary’s outcome.

Despite the deepfake, Biden won New Hampshire handily as a write-in candidate. Still, experts are warning about the possibility of more AI-generated misinformation in Georgia and elsewhere ahead of the Nov. 5 election. This month, a nonprofit anticorruption organization called RepresentUs released a video featuring Rosario Dawson and other actors urging viewers not to fall for such scams.

“AI gives us the ability to create images, video and audio with nothing more than a short text prompt,” said Mike Reilley, lead trainer for the RTDNA/Google News Initiative Election Fact-Checking training program. “That’s a great thing, but in the hands of bad actors, it can produce devastating results.

“Deepfake video, images and audio,” Reilley added, “can spread quickly through social channels and make candidates appear to say and do things they actually didn’t.”

Sophisticated deepfakes can also play off voters’ confirmation biases or their tendencies to interpret things as confirmation of their existing beliefs, said Anthony DeMattee, a data scientist with the Carter Center’s Democracy Program.

“They are going to hit you up with a particular message that reinforces your prior beliefs, in which case that instinct won’t necessarily tell you to go fact-check,” said DeMattee.

Of particular concern are AI-generated deepfakes being launched on Election Day, said Joe Sutherland, director of Emory University’s Center for AI Learning.

“When it comes down to Election Day, there is not a lot of time to rebuke falsities,” said Sutherland, who served in the White House’s Office of Scheduling and Advance in the Obama administration.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution asked Sutherland, DeMattee and Reilley how voters can detect AI-generated misinformation. Here are some of their suggestions:

- Use free online deepfake detection tools, such as TrueMedia.org

- Search suspicious messages for misspellings, grammatical errors and unattributed assertions

- Inspect images of people for disproportionate, distorted or missing features

- Study videos for pixelation, lip-synching and awkward movements

- Check with credible sources, including local and state election officials

About the Author