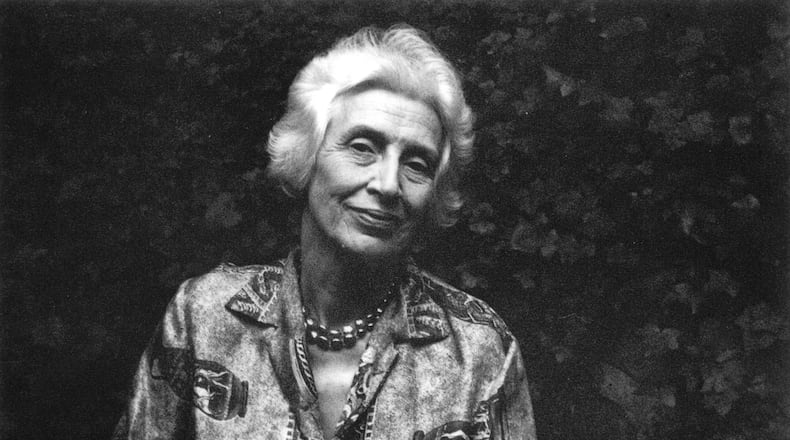

A white woman in the North Georgia mountains writing about racial injustice was a rare thing in the 1940s. That’s why Lillian Smith is having something of a renaissance right now.

In recent years Smith has been the subject of a Hal Jacobs documentary, a historical marker honoring her memory was installed in Clayton and the Southern Literary Trail created a touring exhibition devoted to her life and work. A biography by Keri Leigh Merritt is slated for publication next year.

Smith’s best-known work is “Strange Fruit,” a novel about an interracial romance published in 1944. Although sales were banned in several states, it was a runaway bestseller. Three years later she published “Killers of the Dream,” a memoir that explored growing up in a segregated South.

“Lillian Smith was a gutsy voice of conscience at a time when a lot of white Southerners didn’t feel like they could speak out about things,” said Jim Auchmutey, a board member for the Wren’s Nest where the Lillian Smith exhibition is on view through Oct. 26.

“She also shows you that there were always people bothered by the racial status quo in the South. A lot of white people knew it wasn’t right, but they just didn’t quite know what to do about it. Or they didn’t have the courage to speak out against it, and she did.”

The small exhibition features informational placards, enlarged photographs and samples of Smith’s work. On its closing day, Matthew Teutsch, director of the Lillian E. Smith Center at Piedmont University, will give a talk on the author. Tickets are free, but registration is encouraged at wrensnest.org. The exhibit moves to the Georgia Writers Museum in Eatonton next.

Smith’s legacy lives on in the Lillian Smith Book Awards, given by the University of Georgia Libraries. Established in 1968 to recognize the best writing on social justice, it has been bestowed upon literary luminaries Natasha Trethewey, Tayari Jones, Frye Gaillard, Anthony Grooms and Melissa Fay Greene, among others.

Earlier this month, the award was presented to two authors at a ceremony at Decatur Library’s Georgia Center for the Book, a partner in the award program, along with the Southern Regional Council and Piedmont University.

Recipient Susan Crawford is a Harvard law professor who specializes in climate change and public leadership. Her book, “Charleston” (Pegasus Books, $28.95), explores the intersection of race and climate change in the coastal city where rising sea levels threaten the lower peninsula, where nearly 7 million mostly white tourists visit every year.

Credit: Wren's Nest

Credit: Wren's Nest

The other recipient was journalist Victor Luckerson, author of “Built From the Fire” (Random House, $25), about three generations of a family who endured the 1921 massacre of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the urban renewal plans that decimated their community in the ’70s. Now a family member represents the neighborhood in the Oklahoma Legislature and works with activists trying to revive the area.

The award is an appropriate homage to Smith, who some thought risked being forgotten by future generations.

“As far back as the 1940s, she became this voice of displeasure with the racial status quo in the South, and it made her reputation. It made her very controversial and made her a notorious author,” Auchmutey said.

Credit: Bo Emerson

Credit: Bo Emerson

Some people believe that’s why she was nearly forgotten — she was scrubbed from the annals of literary history because of her views. But Auchmutey disagrees.

“I think it’s just the passage of time,” he said. “If she had never done any of that, we would really not know who she is. The only reason we know who she is is because she wrote ‘Strange Fruit’ and other things to do with race.”

Suzanne Van Atten is a book critic and contributing editor to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. She may be reached at Suzanne.VanAtten@ajc.com.

About the Author