Many trekkers who set out on the Appalachian Trail eventually ditch some of the heaviest baggage that is slowing them down — and not just the gear spilling out of their backpacks.

Hiker John Turner uses an old dictum of philosophy to explain the process of unloading psychological burdens.

“A 9th-century Buddhist master advises: If you meet the Buddha on the road kill him,” he says. “That’s not meant literally. The Buddha represents your illusions, all the wrongheaded ideas you have about yourself.”

For adventure-seekers in our anxious, stressed-out age, that figurative, symbolic kind of Buddha, it turns out, proves as plentiful as black bears — and a lot more demoralizing — as Turner discovers in his memoir “Killing the Buddha on the Appalachian Trail: Walking on Through Self-Doubt and Aging” (UGA Press, $29.95).

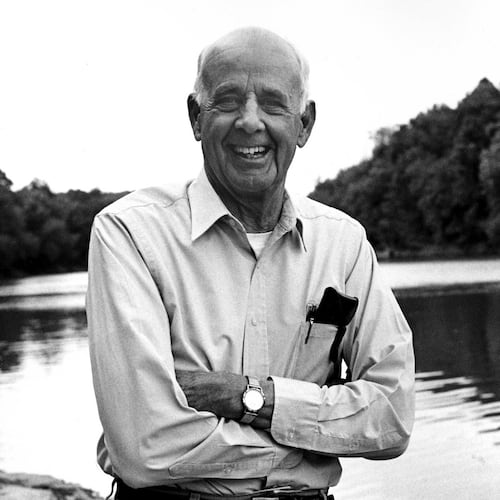

At 68 years old, Turner, a retired newspaperman and communications specialist who lives in Blue Ridge, embarked on the 2,193-mile trek from Georgia to Maine, commonly referred to as AT. Along the way he kept detailed journals which proved useful in writing the book.

With droll, self-effacing humor, he recounts his encounters with wildlife (a raven, five bears, a rattlesnake, a swarm of black flies), rock formations (slippery, sandstone shelves and human-made cairns) and memorable fellow hikers who form what they call a “tramily,” with “trail names” befitting their quirks such as Moonrise, Quicktime and Merlot. (Turner’s is Raven.)

“The trail is an experience of extremes because you spend several hours in solitude,” Turner says, “and then you encounter another person who is like-minded, who shares the same goal you have, so the bonds of camaraderie you forge out there are intense and quick. A gossip network runs up and down the trail with hikers keeping each other informed of bears, rough weather or other hazards. Romances bloom, and there are the occasional trail weddings.”

Beginning in the forested Southern mountains and plodding his way north over ever-changing topography with stunning views vividly described, he gives readers a crash course in the history of the trail and its rich culture and traditions. Along the way, Turner, who holds a degree in philosophy from Mercer University, ruminates on why we walk, on how we nurture (or despoil) the Earth and on the many Buddhas he has to kill, rendering his account much more than just a glorified Fitbit printout.

Credit: UGA Press

Credit: UGA Press

“This is not a typical AT book,” says Susie McNeely, one of a handful of hikers who have completed the famous Triple Crown of long-distance hikes — the Appalachian Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail and the Continental Divide Trail. She also recently completed the Shinetsu Trail in Japan, which was inspired by the Appalachian Trail.

“What John has produced is something that is as unpredictable as the trail itself. I would come to a passage in his book about a section of the trail I know well, and I would anticipate: ‘OK, I know what he’s going to say about that.’ But I would be wrong. He would have some meditative musing that caught me off guard and made me think about the trail in a whole new way.”

First envisioned by forester Benton MacKaye as a chain of linked mountain camps to provide a respite from city life for a week or so of salutary camping, the Appalachian Trail was hacked out of the wilderness by 1937 and quickly drew all-or-nothing types who wanted to tackle the entire thing.

Those who do it all at once, a journey that typically lasts a little less than a year, are called thru-hikers, and those who take it in pieces are section hikers. Turner falls into the latter camp. He hiked in spurts, some as short as a day covering only a few miles and others nearly a month long and more than 200 miles in length.

“Being an Appalachian Trail section hiker is a bit like being Bill Murray in the movie ‘Groundhog Day,’ because day one on the trail happens over and over and over,” he says. “That means one stand-out difference is that section hikers rarely, if ever, develop the spring-steel ‘trail legs’ that allow thru-hikers to power up and down mountains at a 3-mph pace, 20 to 25 miles per day, day after day, week after week. I could only admire with envy how they could climb a mountain as effortlessly as a white-tail deer while I huffed and puffed like an antique steam engine.”

Step by step, though, he made it. Turner jubilantly finished a couple of years ago, just 10 days after his 73rd birthday. (The oldest known hiker to finish the trek was M.J. Eberhart, the “Nimblewill Nomad,” at 83.)

Credit: John Turner

Credit: John Turner

“It’s the same trail, no matter how one hikes it,” Turner says, “but everyone hikes it differently.”

Bill Bryant, who also completed the trail as a section hiker, says Turner captures the day-to-day grind and grandeur of the undertaking. “What John demonstrates is the sheer persistence it takes to plow on through a litany of challenges every single day,” he says. “You can’t have a bad day and decide you’re quitting because the next day might be a good one. You might miss some trail magic.”

The phenomenon known as “trail magic” can take the form of a raven circling overhead or containers of clean drinking water mysteriously appearing at a camp-site. “It’s always unexpected,” Turner says, “and it can restore your faith in your fellow man.”

Wildlife is not the only nature a hiker confronts — there is also human nature, for better or worse. Merlot might share a snoot from her thermos, but not everyone enhances the sylvan tranquility of a campsite. Turner’s funniest chapter involves a hiker known as Skeedaddle, a manic, foul-mouthed chatterbox nicknamed for the flight response he inspires in other hikers. But even the annoying Skeedaddle has lessons to teach. At the end of each day, resting his tired feet, Turner ruminates on other unpleasantness, including some of the setbacks in his own life. His raw honesty testifies to the healing properties of wilderness and adds to the power of the book.

Turner grew up in Rome, the son of an architect and a secretary. He dreamed of becoming a writer, and tried his hand at it, with mixed results. He worked for The Macon Telegraph and The Atlanta Journal. But “…I was way behind by most measures of American success,” he writes, “I had a house foreclosure in my past, a failed stint as a weekly newspaper editor, years of unemployment sprinkled with odd jobs. … All while I chased the dream that had sent me to Africa right out of college in pursuit of a story I thought I could tell. A story, it turned out, no editor wanted to read, much less publish.” Rejection letters piled up.

So many false starts, engendering so much self-doubt. Those Buddhas needed killing, and they began to die, one after another, on ridgelines and summits.

“The Buddha is all about your perception of self,” Turner riffs. “You can think you’re the greatest hotshot, or you can think the obverse — that you’re not worthy. Both thought processes stand in the way of succeeding as a hiker. Over and over, every day on the trail, you have to kill the Buddha. You have to realize that the Buddha is just your thoughts, that those illusions are not real. What is real is the air you’re breathing in and out of your lungs and your feet on the ground, putting one in front of the other.”

Taken together, these thousands of steps add up to a compelling memoir of an extraordinary achievement that is, happily, very real.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured