In the moments before the start of the first Selma to Montgomery March on March 7, 1965, Andrew Young gathered several of the key organizers in a field for prayer.

Among them were Hosea Williams, John Lewis and local activist Amelia Boynton, who pushed the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to come to Selma to join their fight for voting rights.

While they all knelt, Young remained standing and lifted his right hand toward heaven.

“I prayed over them to get the march started,” said Young, now 92. “I prayed for safety. I prayed for courage. I prayed for the troopers and I prayed for George Wallace. I prayed that these people realize that we’re all brothers, we’re all American citizens and this is a right for which we have fought and died for many years.”

Lewis and Williams went to the front of the line to begin their initial march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

Young went to the back, a strategic move ensuring that he would at least not get arrested.

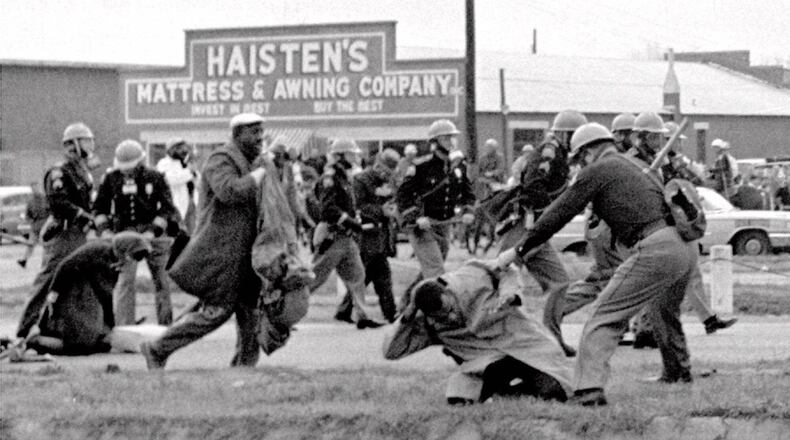

The intended peaceful march turned into what became known as “Bloody Sunday,” as Alabama state troopers and Sheriff Jim Clark’s posse attacked hundreds of demonstrators as they crossed the bridge.

The confrontation, stamped by the iconic images of Williams and Lewis being beaten by state troopers, would turn national attention to the South’s civil rights struggle and immediately laid the groundwork for the August 1965 passage of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibited the suppression of voting rights based on race.

“We always felt that we needed the support of the court for what we were doing. But the power was in the marching,” Young said. “The power was in the willingness to stand up to the suffering. And take it.”

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Moving forward

This weekend will mark the 60th anniversary of Bloody Sunday.

Organizers in Selma and Montgomery have planned dozens of events, from workshops and panels to a multiday march from Selma to Montgomery. On Friday, U.S. Rep. Nikema Williams is leading a wreath-laying with the Southern Poverty Law Center at the Civil Rights Memorial Center in Montgomery, in honor of Lewis.

On Sunday, Sen. Raphael Warnock will preach at Tabernacle Baptist Church in Selma, before crowds re-create the crossing of the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

But this year’s marking of the anniversary comes against the backdrop of attacks on voting rights, education and diversity programs, as the country might be on the verge of eroding many of the gains the march helped build.

At remarkable speed, President Donald Trump has pushed to unravel DEI — diversity, equity and inclusion — programs across the federal government, to usher in what he called a “colorblind and merit-based” society.

Last month, Trump suspended a federal scholarship program supporting agricultural students at 19 HBCUs, including Fort Valley State University. He hastily reinstated the program after intense backlash, but observers fear more cuts are likely to come.

Warnock, pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, said something ominous is happening to a country when Trump and Elon Musk, “an unelected billionaire, can take a chain saw to critical government services … to squeeze the voices of our people out of their democracy.”

Appointed by Trump to head the newly created Department of Government Efficiency also known as DOGE, Musk recently even floated the idea of pardoning Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis police officer convicted of murder for the 2020 killing of George Floyd.

“There’s no question that we are seeing an unabashed assault on human rights and civil rights. This way in which the very idea of diversity and equity and inclusion has somehow been made a dirty word is a terrible development in our politics,” Warnock said. “Selma was about diversity and inclusion. It was about making sure that everybody had a place at the table and a voice in our democracy. We cannot shrink back from those ideals. This idea that we would turn our backs to the very idea of diversity itself is un-American.”

Margaret Huang, president and chief executive officer of the Southern Poverty Law Center, said while it is good to reflect on the legacy and efforts of the foot soldiers who advanced civil rights protections, it is also important to look forward.

“We are all contemplating how we push back against the growing authoritarian efforts of this administration to demoralize, overwhelm and create chaos and fear. It is affecting everyone,” Huang said.

“People across the country are feeling the implications of these very bad actions by this administration. This is a moment for us to think, not who is going to come and save us, but what am I going to do to stand up.”

‘Good Trouble, Necessary Trouble’

Williams now holds John Lewis’ congressional seat. On Tuesday, when Trump addressed a joint session of Congress, she stormed out of the speech wearing a “Good Trouble, Necessary Trouble,” shirt. She said the country is in the middle of a new civil rights movement.

“It’s up to us to decide the future of this country,” Williams said. “As we reflect on the 60th anniversary of Bloody Sunday and what happened in Selma, it is a reminder that I wouldn’t even be serving in this body had it not been for the people who put their lives on the line for me and others to have the right to vote and serve in public office.”

Credit: Steve Schaefer/AJC

Credit: Steve Schaefer/AJC

On Wednesday, House Democrats reintroduced the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, a bill requiring states with histories of voting rights violations to receive federal approval before changing their voting laws.

In a news conference announcing the bill’s reintroduction, Rep. Terri Sewell, D-Ala., said state legislators proposed more than 300 bills in 2024 to make it harder for Americans to cast ballots by closing polling locations, curbing early voting, ending vote-by-mail and imposing stricter voter identification requirements.

“We need to be expanding access to the ballot, to make it easier for folks to vote at every opportunity. Not easier for Democrats, not easier for Republicans but easier for all Americans to show up and make their voices heard,” Williams said. “The more people that we have engaged in our democracy, the more people showing up, the better we are. That is who we should be as a country.”

‘Willing to die’

The 1965 march was years in the making as local Selma activists like Amelia Boynton fought for voting rights in a town where only 300 African American residents were registered as voters.

The march was organized by King’s SCLC and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to promote Black voter registration and to protest the killing of Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was shot by a state trooper on Feb. 18.

Credit: Bettmann Archive

Credit: Bettmann Archive

“We came to the highest point on the Edmund Pettis Bridge,” Lewis said many times when recounting the march. “Down below, we saw a sea of blue. That’s when Hosea asked me, ‘John, can you swim?’ and I said, ‘Not very much, can you?’”

As the demonstrators crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, they were ordered by the police to disperse. When they stood in place, the troopers charged at them.

Credit: AP file

Credit: AP file

The police fired tear gas at the crowd and charged on horseback. More than 50 demonstrators were injured, including Lewis, who suffered a fractured skull.

A photo of Boynton lying unconscious on the bridge became another enduring image of the day.

“These people were willing to die and they were going to march anyway,” said Elisabeth Omilami, the daughter of Hosea Williams. “My father was willing to die. He was a fearless individual with a staff that was fearless. He always said that he met Jesus when he met Martin Luther King, because he adored him that much. They were all willing to give up their lives.”

Credit: Jenni Girtman

Credit: Jenni Girtman

Judgment in Selma

The day of violence was covered in newspapers across the country and broadcast on national news, outraging many Americans.

Andrew Young remembers a surreal national moment when ABC News interrupted its Sunday night airing of the movie “Judgment at Nuremberg,” which explored the bigotry, war crimes and complacency of soldiers “following orders” in Nazi Germany to play live, parallel footage of Bloody Sunday to 50 million Americans.

On March 15, 1965, during a joint session of Congress, President Lyndon B. Johnson asked lawmakers to pass what is now known as the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In his speech he repeated the phrase that symbolized the movement: “We shall overcome.”

On March 21, marchers made their final attempt to walk from Selma to Montgomery. They arrived on March 25.

By the end of that summer, Johnson would sign the Voting Rights Act.

Credit: ap

Credit: ap

“The only time I saw Martin Luther King shed a tear was when we were sitting in Dr. Sullivan Jackson’s home looking at his television, and Lyndon Johnson came on and said he was introducing a voting rights bill and said ‘We shall overcome,’” Young said. “I was sitting on the floor and Martin was sitting in the chair above me. That was a moment.”

Become a member of UATL for more stories like this in our free newsletter and other membership benefits.

Follow UATL on Facebook, on X, TikTok and Instagram.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured