The lore of the “Dark Sisters” has haunted the fictional Georgia suburb of Hawthorne Springs for generations. The legend isn’t only a ghost story or a vision experienced through dreams. A sighting of the Dark Sisters — two women facing in opposite directions with their hair braided into a single plait binding them together — foretells an illness that will soon plague a woman in this tight-knit, oppressively religious community. And sometimes these sick women die.

Atlanta author Kristi DeMeester delivers a rousing work of feminist literature with her third novel, “Dark Sisters,” a vengeful gothic horror story that spans from the witch hunts of 1750 to an affluent preacher’s stronghold on the same community in the 21st century. Weaving together three timelines, DeMeester’s narrative magnifies a Christian patriarchy that not only oppresses women but has derived power from them for generations.

Camilla Burson is a preacher’s daughter in 2007 who is living a double life. On the outside, Camilla is an 18-year-old churchgoing fashionista on the cusp of participating in a “purity ball” — a ceremony where daughters pledge to their fathers that they will remain sexually abstinent until marriage. But inside, she is brimming with an innate thirst for equality and freedom from the intense pressure to embody female chastity mandated by her father.

DeMeester paints a comprehensive portrait of the mental conditioning used to keep the women of Hawthorne Springs in line. Their overarching obsession with beauty, thinness and luxury goods is rooted in the belief that men don’t cheat on beautiful women; therefore, it is the female’s responsibility to ensure their husbands do not sin. It’s an exhausting expectation that shapes every facet of their lives.

Mary Shephard is a new mother in 1953 who is also living obscured. She whiles away her days baking bread and caring for her infant daughter, unable to pinpoint the source of her dissatisfaction. But her description of feeling like there is “broken glass shoved inside me and every time I move, I bleed,” succinctly conveys her despair.

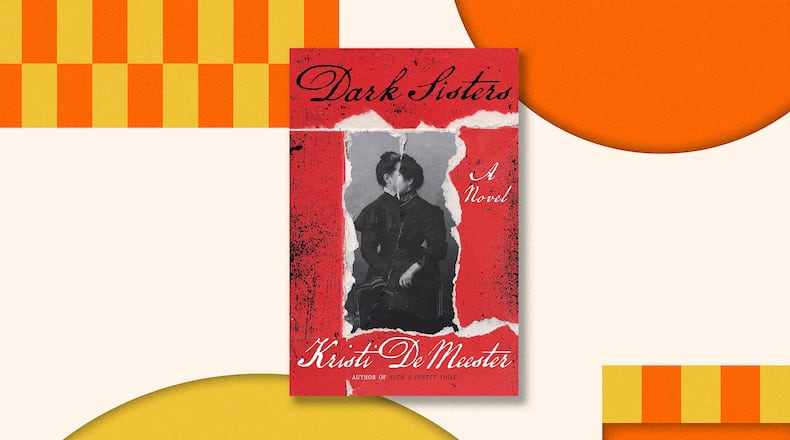

Credit: St. Martin's Press

Credit: St. Martin's Press

While it takes Camilla a while to figure out that the designer clothing her father generously gifts her is a distraction, Mary knows from the moment her husband brings home a sparkling new washer and dryer that material objects won’t fill her void. Instead, she asks him for permission to get a part-time job — where she meets a beautiful young woman who helps Mary define her identity crisis.

Unfortunately, the expectations that Mary be modest, obedient, virtuous and “cultivate a meek and quiet spirit” are precisely the same constraints placed on Camilla more than 50 years later. Mary discovers things about herself that threaten her place in the community, as do Camilla’s findings once she probes into the history of her father’s church and learns what truly happens when wayward women who don’t adhere to religious doctrine are sent on “retreat.”

While Camilla and Mary must behave a certain way to remain accepted by their community, Anne Bolton and her daughter, Florence, are forced to flee their home in 1750 when the town leaders start burning women under the guise of flushing out witchcraft. On the path to freedom, Anne develops a spiritual connection with a majestic black walnut tree that radiates enough power to make the air around it “expand and contract like some great, living creature drawing breath.” She builds a homestead in its shadows.

Anne, Mary and Camilla are distinctive characters with differing trajectories. Yet the fundamental crisis each woman must overcome is the same. Anne struggles to hold on to her homestead once men from a neighboring town decide they want her fertile land for themselves. Mary has feelings for a woman that consume her from the inside out as she struggles against her husband’s control over her life. Camille is the final generation who must figure out how to separate from Hawthorne Springs’ patriarchal stronghold before she is imprisoned by convention like the generations before.

The three timelines alternate as the stories convene around the tree. The Bolton women experience the tree spirit as both generous and demanding. It blesses them with material abundance but expects transparency and truth in their worship. Yet even after fleeing for their lives, Florence retains her Puritanical beliefs and condemns Anne’s connection to the tree as obverse to Christianity. From their dispute, the legend of the Dark Sisters is born.

By the time Camilla is coming of age three centuries later, the Dark Sisters is received as more of a terrifying lesson than a ghost story. In this macabre and evocative description that is one of many sprinkled throughout the narrative, the Dark Sisters are rumored to devour their victims by pulling “their mouths apart with their hands until their jaws break and then slurp them up whole.”

Camilla learns the legend as a child and carries “her fear like a second skin, slipping it on and off from year to year until she was old enough to understand” that the story exists to scare her into behaving a certain way.

Except in DeMeester’s speculative tale, this myth is real. The tree still demands worship for bestowing Hawthorne Springs with generations of wealth. As all three women battle sickness, Camille uncovers generational secrets that threaten the very foundation of everything she knows and loves. Twisty, gory and spellbinding, Kristi DeMeester has a lot to say about the nature of good and evil as her characters seek freedom from the patriarchal stronghold that defines their existence.

FICTION

“Dark Sisters”

by Kristi DeMeester

St. Martin’s Press

336 pages, $29

AUTHOR EVENT

Kristi DeMeester. Book launch 6:30 p.m. Dec. 9. Free with RSVP. FoxTale Book Shoppe, 105 E. Main St., Suite 138, Woodstock. 770-516-9989, www.foxtalebookshoppe.com

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured