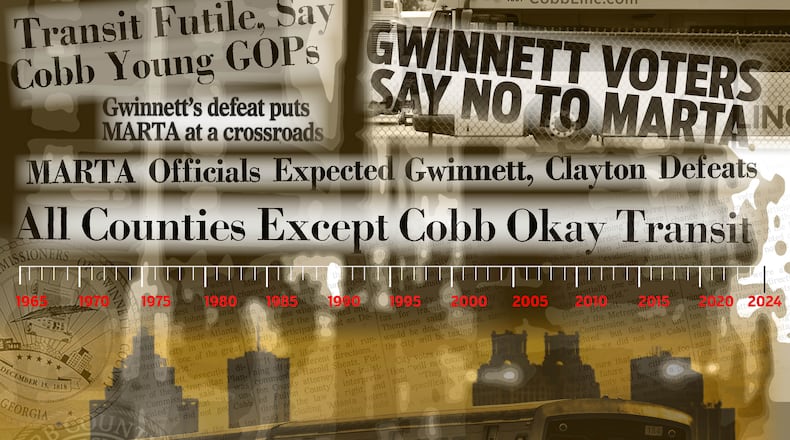

For more than half a century, residents of Georgia’s second and third most populous counties have repeatedly rejected penny sales taxes for transit expansion. But starting Tuesday, when early voting begins, Gwinnett and Cobb counties will propose those taxes again — this time, to fund the most far-reaching and costly plans yet.

The main difference: neither plan includes heavy rail or expands the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority.

Voter approval would reverse years of historical precedent and reflect both counties’ evolution into diverse, largely dense suburbs.

Or maybe it would just mean MARTA was the problem all along.

The support of each county’s relatively new Democratic majorities is key to the success of the latest transit plans, though this group’s engagement remains unclear.

Miatta Tarawally, 31, has lived in Snellville since she immigrated as a child from Sierra Leone, but neither of Gwinnett County’s two recent efforts were on the former Barack Obama voter’s radar. Nor did she know, less than two months before Election Day, about the county’s latest plan. But she likes the idea.

“It would be good if buses were here,” Tarawally said in the parking lot of the Centerville Walmart where, unbeknownst to her, a new high-frequency bus would run.

Atlanta’s suburbs have mounted stubborn opposition to transit ever since they were first asked to support MARTA in 1965. The objections are so well established that after old rail cars were dropped into the ocean to create reefs recently, one online commenter noted “Fish get MARTA before Cobb does.” Voters’ criticisms have run the gamut, from inflammatory sentiments about the race and class of riders to denouncements of MARTA’s spending and operations.

The two counties look different today than they did in 1965 when conservatism and white flight fueled growth. Both counties now lean Democratic, a party whose national platform calls for transit expansion. The tax questions on the ballot this November could also benefit from the relatively high turnout of a presidential election.

But those factors were true four years ago when Gwinnett voters nevertheless sank a transit proposal. It failed largely because Democrats’ support for transit was divided, data shows.

This time around, proponents are stressing that Cobb and Gwinnett would keep running their own transit systems themselves, without MARTA. The plans are similar and both call for the addition of rapid bus routes, extending service hours and bus frequency and making on-demand rideshares available countywide.

Opponents have balked at the plans’ 30-year length and the costs, potentially more than $30 billion if both plans are approved. They point to low ridership as evidence of suburban disinterest and don’t think the new transit offerings will change how people want to travel.

“It doesn’t work for most people, which is why people have cars,” said Jim Jess, a member of the Franklin Roundtable, a group that grew out of the Georgia Tea Party and has been leading transit opposition in Cobb.

Jess believes that when voters hear the plans, they’ll agree with him. Still, the challenge for him — and his opponents — is simply reaching voters: So many people he talks to are learning about it for the first time, he said.

“It is all about the ground game,” he said. “Who can get their voters to the polls?”

Credit: Ben Hendren

Credit: Ben Hendren

‘The wrong people’

MARTA was supposed to connect the metro area. Those plans hit snags almost immediately.

Right out of the gate, Cobb refused to ratify the transit agency’s creation. Gwinnett and Clayton voters then defeated a penny sales tax for MARTA in 1971. MARTA plowed ahead with a more condensed system, setting the stage for all the subsequent transit debates in a metro that’s now one of the most congested in the world, in part because of its limited regional transit options.

The rise of Atlanta’s suburbs is tied to people’s changing attitudes on transit, said Kevin Kruse, who wrote a book about racial politics in the region and who penned an essay for 1619 Project arguing segregation led directly to today’s traffic jams.

Desegregation turned buses into a battleground. People moved to the suburbs to physically get away from integrated spaces in the city, Kruse said. Once there, residents weren’t interested in creating new spaces that would have to be integrated, too.

“There’s a real rejection of all kinds of public services, especially transportation, something that’s going to break down the intentional isolation of the suburbs,” Kruse said. “I call it the suburban secession.

“They want to be a separate entity in every way.”

During the initial push for MARTA expansion, he said, a Cobb County commissioner talked about stocking the Chattahoochee River with piranhas to keep MARTA away. In Gwinnett, there were bumper stickers that simply read NNIG — No n-words in Gwinnett.

Racist arguments against transit have popped up virtually every time it’s been reconsidered.

When Gwinnett put the issue to voters in 1990, the county was 94% white. In widely quoted remarks and letters to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, residents said transit from Atlanta would bring “the wrong people” to their suburbs. They painted the big city as a place with a reputation for murder, rape and drugs. A then-commissioner said: “One of the worst fears is bringing people out of Atlanta, the minorities.”

MARTA backers tried to capitalize on the forthcoming Olympic Games, saying the event would inspire suburban pride in Atlanta, but opponents were dismissive.

“The people who moved here, the vast majority of them moved from Atlanta,” one Snellville man said at the time. “They moved here to get away from the problems that Atlanta has, real or perceived.”

Two weeks before Election Day, a man was shot to death at the Civic Center MARTA station in downtown Atlanta. The same day, the AJC began polling Gwinnettians on the transit question. Almost 60% of those polled were opposed.

Several respondents later said they didn’t cite race as a major factor in their opinion because they suspected the pollster was Black.

“I hate to think I have prejudices, but I do,” a 36-year-old white woman told the AJC.

The day before Election Day, to kick off the afternoon rush, a tractor-trailer overturned on Interstate 85 in Gwinnett. Fuel spilled. Three cars caught fire. Traffic backed up for six miles.

But the next day, transit expansion fared even worse than the polls predicted. About 70% of voters shot it down. The issue died in Gwinnett for almost three decades.

Bipartisan support — and opposition

Charlotte Nash voted against transit expansion in 1990.

Then Gwinnett’s director of finance, she later told the AJC the plan amounted to “a nebulous promise.” By 2019, Nash had become the county commission chair. Gwinnett’s population had more than doubled, with white people in the minority.

Under Nash’s leadership, the county commission floated a transit tax again.

The 2019 plan would have extended MARTA rail through less of Gwinnett than in 1990. It would also have dramatically expanded the county’s bus system. The proposed contract with MARTA would have given the county commission an unusual amount of control over how revenue from Gwinnett would be spent.

But the county commission decided to call a special election in March 2019 for the transit question instead of adding it to the November 2018 midterm ballot. The stand-alone election seemed to bring passionate MARTA opponents to the polls, while many who might have checked “yes” on a midterm ballot stayed home.

Race and class divides remained an issue, as some voters told a national media outlet transit would bring panhandlers and “riffraff.” One woman was quoted saying the plan would subsidize undocumented immigrants and people who can’t manage their money well enough to buy a car.

But support, and opposition, was beginning to cross racial and partisan lines.

Some Republican politicians like Nash and business people backed MARTA expansion, citing benefits to employment and economic development. They formed the bipartisan “Go Gwinnett” campaign — and were surprised to find many Black Democrats in south Gwinnett were not on board, recalled Republican operative Brian Robinson, a former Go Gwinnett spokesman.

“You could target Democratic neighborhoods, for example Black neighborhoods ... and they would say: ‘We moved here to get away from that,’” Robinson said. “This idea that Black people are for it, white people are against it, it really wasn’t true.”

The county tried again the next year, hoping to benefit from record turnout in the 2020 presidential election. The referendum failed by a quarter of a percent of the vote.

The AJC analyzed the results of the 2020 referendum in Gwinnett and found the precincts with the most Black voters, mainly at the county’s southern tip, reflected the greatest disparity between support for President Joe Biden and the transit tax.

The precincts with the most Black voters overwhelmingly supported Biden, but the transit question won far slimmer majorities there, defying expectations that transit would ride the blue wave.

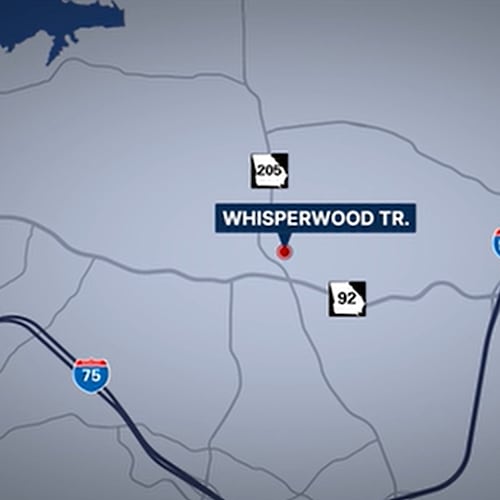

Gwinnett Commissioner Ben Ku, whose district now includes that area and who has long advocated for transit expansion, said the 2020 plan didn’t offer Centerville any new routes. He’s not sure whether voters knew that, or whether many rejected the new tax because they didn’t know what it was for.

“The problem is, a lot of people don’t know who’s on the ballot, what their ballot is except for maybe the top of the ticket,” Ku said. “The first time they may see it is when they’re in the voting booth.”

Learning from mistakes

Proponents in Gwinnett and Cobb have reason to hope this year will be different.

They say the lessons learned in Gwinnett during the 2019 and 2020 votes have led to better plans. Heavy rail via MARTA, which has been a deal-breaker for many voters, isn’t being considered. And officials in Cobb included support for trails and road safety improvements in a bid to be able to provide something in the plans for everyone, even those who don’t use or plan to use transit.

While Democratic voters who make up the majorities in both counties will be key to the success of either referendum, the coalitions for and against them span the political spectrum. As they did during the recent Gwinnett referendums, business groups support the efforts.

Credit: Olivia Bowdoin

Credit: Olivia Bowdoin

This year’s transit campaign in Gwinnett is operating under the moniker Get Gwinnett Going, but proponents are stressing how different the plan is from the one pushed by Go Gwinnett.

Gwinnett Commission Chairwoman Nicole Love Hendrickson emphasized the vote is on a penny sales tax to fund the plan — not the plan itself.

“The plan itself doesn’t go away if the referendum doesn’t pass,” Hendrickson said.

Having both plans on the ballot at the same time is also likely to help, Cobb Chairwoman Lisa Cupid said. Though the plans differ, they have similar goals of giving residents more options when it comes to their travel choices.

The dual ballot questions also emphasize how each county’s decisions affect the broader region, she said. Greater connectivity throughout the metro helps everyone.

“It just allows us to be a better player in the region,” Cupid said.

Cobb supporters say Gwinnett may have a slight advantage because the recent attempts primed voters to think about transit.

Matt Stigall, a transit proponent who sits on Cobb’s transit advisory board, said it’s progress in his county to simply get the issue on the ballot. He hopes it wins but said the conversation is valuable regardless. It’s getting people to think about how the suburbs could evolve to better meet present and future needs.

“The most important thing is the education that’s happening,” he said. “We’re going to continue to grow. How do we do it?”

— Digital Audience Specialist Mandi Albright contributed to this article.

Learn more about the November 2024 elections

Election day is Tuesday, Nov. 5. Early in-person voting begins Oct. 15 and ends Nov. 1. Check your voter registration information at mvp.sos.ga.gov.

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured