Editor’s note: This story contains offensive language.

Malcolm X’s bases of operations were generally Harlem, Chicago and the Northeast. He rarely ventured South, but there was one memorable trip to Atlanta.

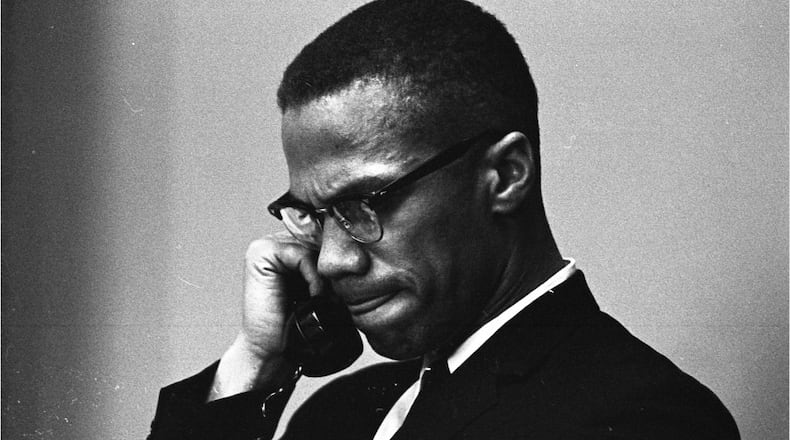

Friday will mark the 60th anniversary of the death of Malcolm X, who has always been a strong cultural figure, often pitted as the opposite of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Since at least the early 1990s, with the theatrical release of Spike Lee’s “Malcolm X,” there has been a renewed interest in Malcolm X’s life through new scholarship.

In 2012, historian Manning Marable won a Pulitzer Prize for his biography “Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention,” which carefully examined the civil rights leader in ways 1965’s “The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley,” did not.

But in another Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “The Dead Are Arising,” which came out in 2020, authors Les Payne and Tamara Payne, Les’ daughter, detail a little-known 1961 trip to Atlanta, at the behest of the head of the Nation of Islam, to meet with leaders of the Ku Klux Klan.

The secret, ill-fated meeting was shockingly embarrassing to Malcolm X, and it perhaps marked the first time he knew he had to leave the Nation.

In “The Dead Are Arising,” the Paynes revised Malcolm X’s origin story with a meticulous and poignant retelling of his life from childhood through his time in the Nation of Islam. The book also exposed how his personal ambitions were shaped by racial trauma, guilt and grief.

In the book, the Paynes wrote the 1961 Atlanta trip began to shift Malcolm X’s belief system. As recounted in the book, Malcolm X was sent to Atlanta by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad to talk with the Klan about building an all-Black colony in Georgia.

Both the Klan and the Nation of Islam favored separation of the races, and Muhammad, who was born in Georgia, thought the hate group might assist his organization in securing a large plot of land.

The meeting was hosted in the home of an Atlanta-based member of the Nation named Jeremiah X, and through scattered government records, secret FBI surveillance, interviews and personal diaries, the Paynes were able to piece together vivid details of the two-hour meeting that both the Nation and the Klan vowed to keep secret.

Malcolm X never talked about it publicly. But it shook him.

The Paynes wrote that the Klan seemed more interested in recruiting members of the Nation to help them kill King Jr., whom they referred to as “Martin Luther Coon.”

Les Payne died before the publication of the book, which earned him his second Pulitzer Prize. Payne, who had worked on the book for decades, wrote that the episode left Malcolm X deeply “embarrassed … and it likely disheartened and shamed him as well.”

Malcolm X had been a public critic of King and rejected the Nobel Peace Prize winner’s direction on race relations. Privately, he respected King.

Former Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young, who worked closely with King in the 1960s said on other visits to Atlanta, Malcolm X would often stop by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference office “hoping to see Dr. King.”

The two never had a relationship but met briefly enough in Washington, D.C., in 1964 to have a photo taken together.

Credit: U.S. News and World Report

Credit: U.S. News and World Report

A year later, on Feb. 5, 1965, just weeks before he was killed, Malcolm X visited with Coretta Scott King in Selma, Alabama, while King Jr. was in jail there for events leading up to Bloody Sunday.

“During his visit to Selma, he spoke at length to my wife, Coretta, about his personal struggles and expressed an interest in working more closely with the nonviolent movement, but he was not yet able to renounce violence and overcome the bitterness which life invested in him,” King Jr. wrote in “The Autobiography of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.”

“There were also indications of an interest in politics; as a way of dealing with the problems of the Negro. All of these were signs of a man of passion and zeal seeking for a program through which he could channel his talents.”

During that 1961 meeting with the Klan, “It did not escape Malcolm’s notice that, in contrast to the Christian Reverend King, the Black Muslims drew not a jot of ire from the one white group in America that was universally despised as devils by all Black people, including Malcolm himself,” the Paynes wrote.

“In fact, the Klan was regarding him and Jeremiah, two key ministers of Elijah Muhammad’s Black Muslims, as potential allies. Muhammad had warned his negotiators about Klan skulduggery, but not even (Muhammad) had anticipated such a cold-blooded request for a joint venture against King. The starkness of the request left Malcolm reeling.”

The book goes on to say that the episode and Muhammad’s willingness to “overlook the long, bloody history, as well as the mounting terror of the Klan struck (Malcolm X) on a deeply personal level.”

Young, who moved to Atlanta in 1961 to work with King at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, said he had never heard the story about Malcolm X’s meeting with the Klan.

Young met Malcolm X sometime between 1957 and 1961, when he was living and working in New York City for the National Council of Churches.

He said Malcolm X truly adhered to his religious teachings and called him one of the “best, purest” people he had ever met.

“I was impressed with how calm, reasonable and studious he was,” Young said. “He was very unemotional about race and race relations. But he was not filled with anger or hate.”

Credit: The National Portrait Gallery

Credit: The National Portrait Gallery

Malcolm X converted to Islam in the 1950s while serving a prison sentence for burglary. After his release from prison, the popular narrative of his life suggests he completely embraced Muhammad and the Nation of Islam, which he used as a foundation to launch some of the era’s harshest critiques of white America and racism.

But after his 1964 pilgrimage to Mecca, just three years after his trip to Atlanta, Malcolm X transformed his worldview, rejected the racially divisive Nation of Islam and changed his name to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

He spent the rest of his life trying to build a new organization while fighting off what he said were death threats from the Nation of Islam.

Four years after the meeting with the Klan, Malcolm X was assassinated on Feb. 21, 1965, by men affiliated with the Nation of Islam during an Organization of Afro-American Unity meeting in Manhattan’s Audubon Ballroom.

His death, sandwiched between the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy and the 1968 murders of Robert F. Kennedy and King, left a gaping hole in the so-called Black militant movement, while elevating Malcolm X, as he stated in his autobiography, into a “martyr.”

Three men were arrested and convicted in the killing. But after spending more than 20 years in prison, two of them — Muhammad A. Aziz and Khalil Islam — were exonerated. The third, Thomas Hagan, was paroled in 2010.

In his eulogy for Malcolm X, Ossie Davis called Malcolm X, “A Prince. Our own Black, shining prince, who didn’t hesitate to die because, he loved us all.”

ABOUT THIS SERIES

This year’s AJC Black History Month series, marking its 10th year, focuses on the role African Americans played in building Atlanta and the overwhelming influence that has had on American culture. These daily offerings appear throughout February in the paper and on ajc.com and ajc.com/news/atlanta-black-history.

Become a member of UATL for more stories like this in our free newsletter and other membership benefits.

Follow UATL on Facebook, on X, TikTok and Instagram.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured