The arrests created headlines throughout Georgia and even beyond.

Two young female correctional officers showed up for their shifts at Calhoun State Prison in South Georgia with suspicious-looking Hot Pockets packages. When the packages were examined, the arrest warrants would later allege, they were found to contain methamphetamine and tobacco.

But what was quickly portrayed by the Georgia Department of Corrections as an example of its vigilance was never criminally prosecuted. The cases against the officers languished for three years until finally the district attorney dismissed them. The reason: The GDC failed to follow one of the basic steps in any drug prosecution. It didn’t submit the drugs for testing.

At a time when state prison officials repeatedly talk of the agency’s “zero tolerance” for drug smuggling, the policy has been severely undermined in Calhoun County, an investigation by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has found, where the Hot Pockets case and many others involving attempts to smuggle drugs into Calhoun State Prison fizzled out because the evidence wasn’t tested at the state crime lab.

Nearly two dozen cases leading to 33 arrests between 2018 and 2021 were disposed of in that manner, the AJC found. The cases were dismissed by District Attorney Joe Mulholland after his office determined that the drugs had not been tested.

Depending on the case, the drugs had to be submitted for testing to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation by either the county sheriff or the Department of Corrections. Of the 23 cases, 11 were investigated by the GDC and 12 by the Calhoun County Sheriff’s Department.

That includes the Hot Pockets case, where a GDC investigator failed to submit the evidence to the lab even though one of the correctional officers was found to have 112 grams of meth, four times the amount necessary to bring a trafficking charge in Georgia, records show.

All told, five prison employees and dozens of other suspected smugglers, some from as far away as Atlanta and Savannah, walked away from charges that included meth trafficking and possession of marijuana with intent to distribute.

The GBI confirmed to the AJC that no evidence had been submitted to the lab for any of the dismissed cases except one.

The bungled investigations represent a serious breakdown for the GDC, raising the specter that lapses in basic evidentiary procedure have torpedoed drug cases at a prison where the contraband problem has spilled into the community, leaving many residents unnerved.

“People I’ve talked to, they’re certainly concerned about it, and they want it stopped,” said Tommy Manry, a former schoolteacher and coach who serves on Calhoun County’s Board of Commissioners. “But it’s not going to come close to stopping until they start prosecuting people like they ought to.”

The question hanging over everything is, who dropped the ball?

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

Attracting smugglers

Contraband has long been a major problem at Calhoun State Prison, a medium-security facility housing more than 1,500 inmates about 30 miles west of Albany in Morgan, the Calhoun County seat.

The prison setting, in a remote and sparsely populated rural area of 4,300 residents, has made hiring qualified correctional officers difficult. It also has proven attractive to smugglers willing to risk arrest for the payoffs that can come from getting drugs, cellphones and other forms of contraband into the hands of inmates.

Residents who live near the prison have been caught in the crossfire, their lives regularly disrupted by drones flying over their homes and strangers running through their yards and fields.

“All kinds of drugs, drones flying like crazy,” Manry said. “We haven’t had any civilians hurt. But I don’t know, looks to me like the prison could do a whole lot more than what they’re doing.”

Trent Tye, a nationally known blacksmith whose home and business, Purgatory Ironworks, are adjacent to the prison, keeps an AR-15, a tactical vest and a high-powered flashlight near his backdoor because, he said, “on any particular evening” he might need them.

“I don’t mean to be overly dramatic, but I don’t know how you can describe it other than a nightly war zone,” he said. “And I stress ‘nightly.’ There have been times where we’ve had people in the woods every night. We literally have hardened criminals running through our backyards armed.”

In an effort to stop smugglers from outside the area, the GDC is paying the Calhoun County sheriff and his deputies $45 an hour to patrol the facility’s perimeter during their off-duty hours.

The arrangement has proven particularly lucrative for the deputies, who are paid between $15 and $18 an hour by the county. In just the first three months of this year, the GDC made payments to Sheriff Josh Hilton and eight of his deputies totaling nearly $127,000, agency records show.

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

Credit: Miguel Martinez-Jimenez

The increased policing seems to be working.

Since 2020, more civilians have been arrested trying to smuggle contraband into Calhoun State Prison than any of the other 35 state-operated prisons, according to an AJC review of news releases issued by the agency as well as by sheriff’s departments throughout the state.

But some county officials have become frustrated by an arrangement that relies on county vehicles and fuel yet has led to few prosecutions.

“The problem is we’re seeing them make arrests, but that’s where the buck stops,” said Mandie Milner, the county’s clerk and administrator.

Untested evidence

The decisions by Mulholland — the DA for the five-county South Georgia Judicial Circuit — are clearly laid out in thin case files filling a box in the Calhoun County courthouse. Some simply indicate that there was no record that the drug evidence had been tested. Others are more direct: “Drugs were not sent to GBI crime lab.”

Mulholland told the AJC that his office has an elaborate system for managing drug cases. The office is regularly notified by the GBI when drug evidence has been analyzed. If nothing shows up over time, letters are sent to the law enforcement agencies responsible for the investigations to remind them to follow through, he said.

If the drugs still aren’t tested after that, he said, “I don’t know what else I can do other than dismiss the cases.”

Credit: Pete Corson

Credit: Pete Corson

Noting that many of the arrests that were ultimately dismissed occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, Mulholland said he believes that could be a reason the evidence wasn’t tested.

“For whatever reason — maybe people were working from home — there definitely was a period where just way too many cases were being dismissed because (the drugs) weren’t being tested,” he said. “I think we’ve gotten that rectified now.”

How effectively the more recent cases are being prosecuted isn’t clear, since hundreds remain pending without indictment or resolution, filling an entire shelf at the courthouse. Most of those cases also pertain to the prison, according to Karen Taylor, the Superior Court clerk.

Even after a grand jury on June 2 heard 35 cases, more than 300 remained pending, she said.

Lori Benoit, a spokesperson for the Department of Corrections, acknowledged in an email that drug evidence from the Hot Pockets arrests was not submitted to the lab for testing. She said the case was one of nine involving 22 defendants pertaining to Calhoun State Prison investigated by the GDC between 2018 and 2021 that were dismissed by Mulholland’s office without prosecution.

She also said not all of the nine dismissals were due to a lack of drug testing, but she could not provide more details. The nine dismissed cases were among 144 investigated by the agency involving contraband or assaults at the prison during that time frame, Benoit said.

The GDC’s statement conflicts with what the AJC found in the court files, which show that that 11 drug cases investigated by the agency in and around the prison were dismissed by the DA’s office because the evidence wasn’t tested. The cases involved 15 defendants, five of them prison employees.

Hilton, the Calhoun County sheriff, claimed his deputies had sent the evidence collected in their drug cases to the state lab. He said he has discussed the matter with Mulholland.

The AJC provided Hilton with documents that gave lack of testing as the district attorney’s reason for the dismissals. Hilton said he would review them but has not responded.

“I mean, we’re spending a lot of time trying to keep dope out of the prison,” Hilton said. “That’s a lot of drugs.”

To check whether the drugs had been sent to the GBI for testing, the AJC submitted requests to the agency for each of the defendants charged in the cases in which lack of testing was cited as a reason for dismissal. The GBI responded that it had no record of substances being submitted for testing in any of the cases except for one.

The exception was a case in which three civilians were arrested at the same time on meth trafficking charges in May 2021. The case, which would have been investigated by the GDC, according to arrest warrants, was dismissed without prosecution in July 2022. The GBI said the testing was incomplete but declined to say when the evidence was submitted.

Hot Pockets arrests

The Hot Pockets case hit the media not long after the two correctional officers, Corlethia Lattimore and Imani Ferguson, were arrested on a February morning in 2020 and immediately fired.

Lattimore was 28. Ferguson was 21. Both women had been on the job less than a year.

The GDC put out a pair of news releases, one for each arrest, identifying the officers and giving the arrest details.

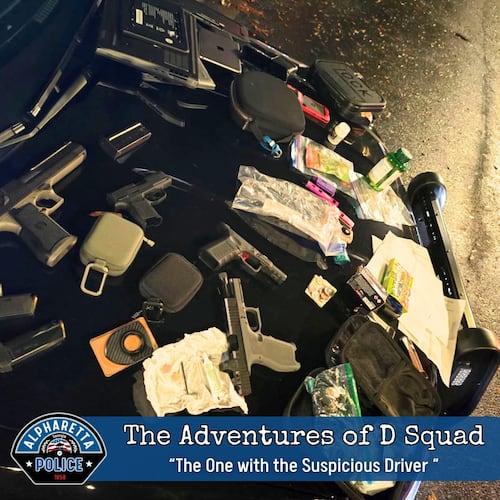

At the same time, the sheriff released a photo that showed a Hot Pockets package and two bundles. One held a white, crystalline substance described by authorities as meth. The other had a leafy brown substance that authorities described as tobacco.

“We stand committed in our continuing efforts to bring justice to those who pose a threat to the safe and secure operations of our facilities, and we applaud the work of GDC’s Correctional Officers,” Benoit wrote at the time in an email that was published in the Macon Telegraph.

Lattimore was charged with trafficking meth, a crime that, based on the amount of the powerful stimulant allegedly in her possession, could have resulted in a mandatory 10-year prison sentence. Ferguson was tied to the tobacco, not the drugs, and was charged with a lesser offense: unauthorized possession of a prohibited item. Both were charged with violating their oaths as officers.

But the case never went forward. After the officers were jailed and released on bond, nothing was done until July 2023, when the charges were dismissed. There was no crime lab report or law enforcement report to support the charges, the dismissal documents state.

Even if the drugs had been tested at that point, the case would have ended unless there were indictments before the four-year statute of limitations ran out in February 2024.

Credit: Ga. Dept. of Corrections

Credit: Ga. Dept. of Corrections

In her email to the AJC for this story, Benoit said the case was handled by a former GDC investigator, Ruby Long, who “notedly took out the warrants; however, she did not submit the evidence to the crime lab.”

Long, who retired in 2023, told the AJC that tracking down the drug testing was not her job because even though she completed the warrants, the case was assigned to another investigator. She also pointed out that every case investigated by the office she worked in — the Office of Professional Standards — is overseen by a supervisor.

Even if the matter somehow fell through the cracks on the GDC’s end, Mulholland’s office could have straightened things out by contacting the agency, she said.

“Clearly, it’s the investigator’s responsibility (to get the drugs tested),” she said. “However, if I were the district attorney, especially in a case like that one, I think I would have been compelled to check the files and say, `What’s wrong with this?’”

Efforts by the AJC to contact Lattimore and Ferguson were unsuccessful. Neither responded to multiple attempts to reach them.

Lattimore’s peace officer certification has been suspended and remains under investigation. Ferguson’s certification has been revoked.

A public defender who was assigned to represent Lattimore at the bond hearing, Erica Austin, said she didn’t realize the case had been dismissed until she received an email last month from a reporter working on this story. She said she then contacted a court clerk in Calhoun County, who confirmed it.

Austin said it is “not necessarily atypical” for the statute of limitations to run out on cases in small counties like Calhoun County, where grand juries meet less frequently than in larger counties.

Court records show that Ferguson was represented by Nicola Cummings, an attorney based in McDonough. Cummings did not respond to repeated messages from the AJC.

The attempt to smuggle the meth and tobacco spotlights the lingering problem of massive staff shortages throughout the state prison system. That often has resulted in the hiring of inexperienced officers, many of whom are women. As the AJC has previously reported, these inexperienced officers can be easily manipulated by prisoners to bring in drugs and other types of contraband.

Manry said he reviewed some of the files for the dismissed cases and was particularly disturbed to see that people arrested on meth trafficking charges had avoided prosecution. He said the situation reminded him of how he felt about disciplining students when he was a teacher.

“It’s like when I taught school,” he said. “If somebody misbehaves and you let that behavior go, you think it’s going to get any better? If they prosecuted these people who did what they supposedly did at the prison, then they wouldn’t keep doing it, I don’t think. It’s the damnedest thing I ever saw. It just defies logic.”

AJC reporter Carrie Teegardin contributed to this story.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured