In preparation for Tuesday’s faceoff on ABC between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump, I recently reread “Inside the Presidential Debates” by Northwestern University professors Newton N. Minow and Craig L. LaMay. (Full disclosure: I have a personally inscribed copy that has a prominent place on my bookshelf).

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

It helped me trace the history of modern presidential debates, which began in 1960, when Congress enacted a one-time-only exemption from the “equal time” law for broadcasting that allowed John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon to appear in four spirited, now historic, televised debates. They stood at slim podiums under hot lights, without notes or any concerns whether their microphones would stay on or be turned off when they were not speaking.

By the 1976 campaign, the Federal Communications Commission figured out a way to make broadcast debates an integral part of all future presidential campaigns. It created a permanent equal-time exemption without any further congressional action. In effect, presidential debates would be characterized as “on-the-spot coverage of a bona fide news event,” and thus not subject to any legal requirement for candidates other than the major party nominees — Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter — to be invited.

The presidential debates also initially needed a veneer of civic virtue, hence their initial sponsorship by the nonpartisan League of Women Voters. But by 1984, with the FCC’s blessing, the broadcast and cable networks began to stage their own presidential debates directly. A new bipartisan group, the Commission on Presidential Debates, was formed in 1987 to manage the negotiations with representatives of the Democrats and Republicans, along with the venue hosts in various selected locations. Minow, a former FCC Chairman under President Kennedy, served as its vice chair for many years.

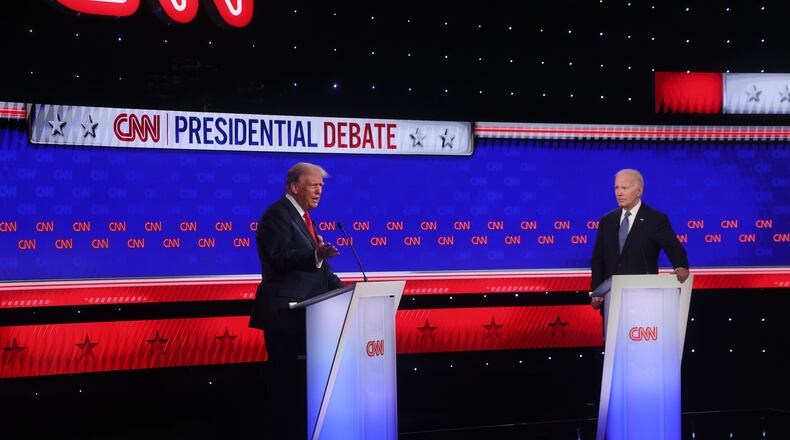

But the passage of time since the book’s publication has taken its toll. This year, the commission has been cast aside in favor of the candidates themselves. Their advisers now reach a direct agreement on debate details, without the need for any intermediary to play a role. That was the case for the impactful Biden-Trump debate in June, which ultimately led to President Joe Biden’s decision not to seek reelection, and with the upcoming Harris-Trump debate (and the scheduled Tim Walz-JD Vance vice presidential debate in October).

So it’s highly unlikely that we will ever go back to a highly managed, genteel debate system now that both parties seem to relish the rough and tumble of proposing and accepting debate terms publicly — grabbing headlines about the debates themselves as Election Day looms with only a few dozen days remaining.

What endures today, and is likely to remain for the foreseeable future, is that the real debate beneficiaries should be the voting public rather than the candidates themselves. Here, the Minow and LaMay book offers some practical wisdom that seems even more salient now, as debates follow something akin to the pregame hoopla and postgame analysis of the Super Bowl.

This year’s Harris-Trump debate carries with it an even heightened sense of hype, as will others scheduled for later in the campaign. After all, presidential debates now make great reality programming for sponsors who want to reach a wide swath of American consumers.

One of the book’s key recommendations for improving presidential debates caught my eye. “The televised presidential debates may be the most important, substantive and revealing moments of the presidential campaign, but they are not enough. Remember when you watch the debates that the debate moderator’s job is to moderate, not to cross-examine the candidates. That job should be for the candidates and the voters themselves.”

The bottom line of the authors’ advice, however, rings truer now more than ever, although no one on screen will say it. “Finally,” they wrote, “after you watch a televised debate, turn your television set (and now all digital mobile devices) off and do your best to avoid the torrent of spin that follows. Give yourself the time — a day, if you can manage it — to talk about the debate with your family, coworkers, friends, neighbors (my update: or post social media comments). Then, if you want, go see what the pundits have to say — and whether you think they got it right.”

Hopefully, the authors can help remind us that a presidential debate is not a championship game. As Minow and LaMay reflected on presidential debates, “For voters, remember that you cannot learn all you need to know.” Rather, the debate should be approached as only one part of a learning process that all voters should commit to before casting their votes by mail or in person on Nov. 5.

Stuart N. Brotman is Digital Media Laureate at The Media Institute and the former president and chief executive of the Museum of Television & Radio in New York and Los Angeles (now the Paley Center for Media). He is a professor in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and the author of “The First Amendment Lives On.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured